interviewprep

Title: Java Part 3

Title: Java

Table of Contents

*. You have thread T1, T2, and T3, how will you ensure that thread T2 run after T1 and thread T3 run after T2?

To ensure that thread T2 runs after T1 and thread T3 runs after T2, you can use the join() method. This method allows one thread to wait for the completion of another.

public class ThreadExecutionOrder {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread t1 = new Thread(() -> {

System.out.println("Thread T1 is running");

});

Thread t2 = new Thread(() -> {

try {

t1.join(); // T2 waits for T1 to finish

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Thread T2 is running");

});

Thread t3 = new Thread(() -> {

try {

t2.join(); // T3 waits for T2 to finish

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Thread T3 is running");

});

t1.start();

t2.start();

t3.start();

}

}

*. How do you handle an unhandled exception in the thread?

You can set an UncaughtExceptionHandler for a thread to handle uncaught exceptions.

public class UnhandledException {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread thread = new Thread(() -> {

throw new RuntimeException("An unhandled exception");

});

thread.setUncaughtExceptionHandler((t, e) -> {

System.out.println("Caught exception from thread: " + t.getName() + " - " + e.getMessage());

});

thread.start();

}

}

*. What is the difference between List<? extends T> and List <? super T> ?

-

List<? extends T>: A list of objects that are instances of T or its subclasses. You can read from the list, but you cannot add to it (exceptnull). -

List<? super T>: A list of objects that are instances of T or its superclasses. You can add instances of T or its subclasses to the list, but reading from it only returnsObject.

*. Can you pass List<String> to a method which accepts List<Object> ?

No, you cannot pass List<String> to a method that accepts List<Object> because of type safety. Generics are invariant in Java.

public class GenericExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> stringList = new ArrayList<>();

// methodAcceptingObjectList(stringList); // This will cause a compile-time error

}

public static void methodAcceptingObjectList(List<Object> list) {

// Implementation

}

}

*. Difference between List<?> and List<Object> in Java?

-

List<?>: A list of unknown type. You can only read from the list, but cannot add to it (exceptnull). -

List<Object>: A list that can hold any type of objects. You can both read from and add to the list.

*. Can we use Generics with Array?

You cannot create generic arrays directly in Java due to type erasure. However, you can use List or other generic collections instead.

// This will cause a compile-time error

// T[] array = new T[10];

// You can use ArrayList instead

List<T> list = new ArrayList<>();

*. Explain Sealed Classes & Interfaces in Java.

Sealed classes and interfaces restrict which classes can extend or implement them. Introduced in Java 15 as a preview feature and standardized in Java 17.

sealed class Shape permits Circle, Square {

}

final class Circle extends Shape {

}

final class Square extends Shape {

}

public class SealedClassExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Shape shape1 = new Circle();

Shape shape2 = new Square();

System.out.println(shape1 instanceof Circle); // true

System.out.println(shape2 instanceof Square); // true

}

}

In this example, only Circle and Square are permitted to extend Shape. Any attempt to extend Shape by another class will result in a compilation error.

To provide answers to the questions along with Java code snippets, let’s go through each question from the provided image and offer a detailed explanation and corresponding code.

*. What is Thread in Java?

A Thread in Java is a lightweight process. It is the smallest unit of a process that can run concurrently with other threads.

public class MyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Thread is running...");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

MyThread t = new MyThread();

t.start();

}

}

*. What is the difference between Thread and Process in Java?

A Process is an instance of a program that runs independently and isolated from other processes, while a Thread is a subset of the process that runs in shared memory space.

// Example code not required as this is a conceptual explanation

*. How do you implement Thread in Java?

Threads can be implemented by either extending the Thread class or implementing the Runnable interface.

// Extending Thread class

class MyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Thread is running...");

}

}

public class TestThread {

public static void main(String[] args) {

MyThread t1 = new MyThread();

t1.start();

}

}

// Implementing Runnable interface

class MyRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Thread is running...");

}

}

public class TestRunnable {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread t2 = new Thread(new MyRunnable());

t2.start();

}

}

*. When to use Runnable vs Thread in Java?

Use Runnable when you want to share the same task across multiple threads or when your class already extends another class.

// Runnable example provided above

*. What is the difference between start() and run() method of Thread class?

The start() method creates a new thread and executes the run() method in that new thread, while run() method just executes in the current thread.

class MyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Running in thread: " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

MyThread t1 = new MyThread();

t1.run(); // This will run in the main thread

t1.start(); // This will run in a new thread

}

}

*. What is the difference between Runnable and Callable in Java?

Runnable is a functional interface that returns void, while Callable returns a result and can throw a checked exception.

import java.util.concurrent.Callable;

import java.util.concurrent.FutureTask;

class MyCallable implements Callable<Integer> {

public Integer call() {

return 123;

}

}

public class TestCallable {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

MyCallable callable = new MyCallable();

FutureTask<Integer> futureTask = new FutureTask<>(callable);

Thread t = new Thread(futureTask);

t.start();

System.out.println(futureTask.get()); // Output will be 123

}

}

*. What is the difference between CyclicBarrier and CountDownLatch in Java?

CountDownLatch is used for a single event while CyclicBarrier can be used for multiple events.

import java.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch;

import java.util.concurrent.CyclicBarrier;

public class TestSynchronization {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

// CountDownLatch example

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(3);

Runnable task = () -> {

latch.countDown();

System.out.println("Counted down");

};

new Thread(task).start();

new Thread(task).start();

new Thread(task).start();

latch.await();

System.out.println("All tasks completed");

// CyclicBarrier example

CyclicBarrier barrier = new CyclicBarrier(3, () -> System.out.println("Barrier reached"));

Runnable barrierTask = () -> {

try {

barrier.await();

System.out.println("Barrier released");

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

};

new Thread(barrierTask).start();

new Thread(barrierTask).start();

new Thread(barrierTask).start();

}

}

*. What is Java Memory model?

The Java Memory Model (JMM) defines how threads interact through memory and what behaviors are allowed in concurrent executions.

// Conceptual explanation; code example not required

*. What is volatile variable in Java?

A volatile variable ensures visibility of changes to variables across threads.

public class VolatileExample {

private volatile boolean flag = true;

public void run() {

while (flag) {

// Busy-wait loop

}

System.out.println("Flag changed");

}

public void stop() {

flag = false;

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

VolatileExample example = new VolatileExample();

new Thread(example::run).start();

Thread.sleep(1000);

example.stop();

}

}

*. What is thread-safety? Is Vector a thread-safe class?

Thread-safety means that a class or method can be used by multiple threads concurrently without causing problems. Yes, Vector is a thread-safe class.

// Vector is synchronized, making it thread-safe

import java.util.Vector;

public class TestVector {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Vector<Integer> vector = new Vector<>();

vector.add(1);

vector.add(2);

vector.add(3);

System.out.println("Vector: " + vector);

}

}

*. What is race condition in Java? Given one example?

A race condition occurs when two or more threads can access shared data and they try to change it at the same time.

public class RaceConditionExample {

private int count = 0;

public void increment() {

count++;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

RaceConditionExample example = new RaceConditionExample();

Runnable task = () -> {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

example.increment();

}

};

Thread t1 = new Thread(task);

Thread t2 = new Thread(task);

t1.start();

t2.start();

try {

t1.join();

t2.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Final count: " + example.count); // Expected 2000 but result may vary

}

}

*. How to stop a thread in Java?

You can stop a thread in Java using a boolean flag.

public class StopThreadExample {

private volatile boolean running = true;

public void run() {

while (running) {

System.out.println("Running");

try {

Thread.sleep(100);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

public void stop() {

running = false;

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

StopThreadExample example = new StopThreadExample();

Thread t = new Thread(example::run);

t.start();

Thread.sleep(500);

example.stop();

}

}

*. What happens when an Exception occurs in a thread?

When an exception occurs in a thread, it will terminate unless the exception is caught and handled.

public class ExceptionThreadExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread t = new Thread(() -> {

try {

throw new RuntimeException("Thread exception");

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println("Caught exception: " + e.getMessage());

}

});

t.start();

}

}

*. How do you share data between two threads in Java?

You can share data between threads using shared objects or data structures.

public class SharedDataExample {

private int counter = 0;

public synchronized void increment() {

counter++;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

SharedDataExample example = new SharedDataExample();

Runnable task = () -> {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

example.increment();

}

};

Thread t1 = new Thread(task);

Thread t2 = new Thread(task);

t1.start();

t2.start();

try {

t1.join();

t2.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Final counter: " + example.counter); // Should be 2000

}

}

*. What is the difference between notify and notifyAll in Java?

notify wakes up one waiting thread, while notifyAll wakes up all waiting threads.

public class NotifyExample {

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void doWait() {

synchronized (lock) {

try {

System.out.println("Waiting");

lock.wait();

System.out.println("Woken up");

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

public void doNotify

() {

synchronized (lock) {

System.out.println("Notifying one");

lock.notify(); // or lock.notifyAll();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

NotifyExample example = new NotifyExample();

Thread t1 = new Thread(example::doWait);

Thread t2 = new Thread(example::doWait);

t1.start();

t2.start();

Thread.sleep(1000);

example.doNotify();

}

}

*. Why wait, notify and notifyAll are not inside thread class?

wait, notify, and notifyAll are part of the Object class because they are meant to be used on shared objects.

*. What is ThreadLocal variable in Java?

A ThreadLocal variable provides thread-local variables where each thread accessing such a variable has its own independently initialized copy.

public class ThreadLocalExample {

private static final ThreadLocal<Integer> threadLocal = ThreadLocal.withInitial(() -> 1);

public static void main(String[] args) {

Runnable task = () -> {

int value = threadLocal.get();

System.out.println("Initial value: " + value);

threadLocal.set(value + 1);

System.out.println("Updated value: " + threadLocal.get());

};

Thread t1 = new Thread(task);

Thread t2 = new Thread(task);

t1.start();

t2.start();

}

}

*. What is FutureTask in Java?

FutureTask represents a cancellable asynchronous computation. It can be used to wrap Callable or Runnable objects.

import java.util.concurrent.Callable;

import java.util.concurrent.FutureTask;

public class FutureTaskExample {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Callable<Integer> callable = () -> {

Thread.sleep(1000);

return 42;

};

FutureTask<Integer> futureTask = new FutureTask<>(callable);

Thread t = new Thread(futureTask);

t.start();

System.out.println("Result: " + futureTask.get()); // Outputs 42 after 1 second

}

}

*. What is the difference between the interrupted() and isInterrupted() method in Java?

interrupted() checks the interrupt status of the current thread and clears it, while isInterrupted() checks the interrupt status of any thread without clearing it.

public class InterruptExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread t = new Thread(() -> {

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

System.out.println("Running");

}

System.out.println("Thread interrupted status: " + Thread.interrupted());

});

t.start();

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

t.interrupt();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

*. Why wait and notify method are called from synchronized block?

wait and notify must be called from within a synchronized block to ensure that the current thread holds the lock on the object before calling these methods.

// Conceptual explanation; code example included in NotifyExample

*. Why should you check condition for waiting in a loop?

To avoid spurious wakeups, it’s essential to check the waiting condition in a loop.

public class SpuriousWakeupExample {

private final Object lock = new Object();

private boolean condition = false;

public void waitForCondition() {

synchronized (lock) {

while (!condition) { // Check in a loop

try {

lock.wait();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

System.out.println("Condition met");

}

}

public void setCondition() {

synchronized (lock) {

condition = true;

lock.notifyAll();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

SpuriousWakeupExample example = new SpuriousWakeupExample();

new Thread(example::waitForCondition).start();

Thread.sleep(1000);

example.setCondition();

}

}

*. What is the difference between synchronized and concurrent collection in Java?

Synchronized collections are thread-safe but have a single lock for the entire collection, leading to contention. Concurrent collections, like ConcurrentHashMap, use finer-grained locking for better scalability.

import java.util.Collections;

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap;

public class CollectionExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Map<String, String> syncMap = Collections.synchronizedMap(new HashMap<>());

syncMap.put("key1", "value1");

syncMap.put("key2", "value2");

ConcurrentHashMap<String, String> concurrentMap = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

concurrentMap.put("key1", "value1");

concurrentMap.put("key2", "value2");

System.out.println("Synchronized Map: " + syncMap);

System.out.println("Concurrent Map: " + concurrentMap);

}

}

*. What is the difference between Stack and Heap in Java?

The stack is used for static memory allocation and method execution, while the heap is used for dynamic memory allocation for objects at runtime.

// Conceptual explanation; code example not required

*. What is thread pool? Why should you thread pool in Java?

A thread pool manages a set of reusable threads (pool of worker threads ) for executing tasks. It improves performance by reducing the overhead associated with creating and destroying threads.

Why use a thread pool?

- Resource Management: Reuses a fixed number of threads, managing system resources efficiently.

- Improved Performance: Reduces the latency associated with thread creation.

- Simplified Concurrency: Provides a higher-level API for executing tasks concurrently.

Example using ExecutorService:

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

public class ThreadPoolExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create a thread pool with 3 threads

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(3);

// Submit 5 tasks to the thread pool

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

String threadName = Thread.currentThread().getName();

System.out.println("Thread name: " + threadName);

try {

// Simulate some work with Thread.sleep

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

System.out.println("Completed: " + threadName);

});

}

// Shut down the executor service

executor.shutdown();

}

}

Explanation:

- ExecutorService: Interface that represents a pool of threads.

- Executors.newFixedThreadPool(int nThreads): Creates a thread pool with a fixed number of threads.

- executor.submit(Runnable task): Submits a task for execution.

- executor.shutdown(): Initiates an orderly shutdown where previously submitted tasks are executed, but no new tasks will be accepted.

*. How to avoid Deadlock in Java

Deadlocks occur when two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting for each other. To avoid deadlock, you can follow several strategies:

1 Avoid Nested Locks

Avoid acquiring multiple locks if possible. If you must, always acquire the locks in the same order.

class A {

synchronized void methodA(B b) {

System.out.println("Thread 1 starts execution of methodA");

b.last();

}

synchronized void last() {

System.out.println("Inside A.last()");

}

}

class B {

synchronized void methodB(A a) {

System.out.println("Thread 2 starts execution of methodB");

a.last();

}

synchronized void last() {

System.out.println("Inside B.last()");

}

}

public class AvoidDeadlock implements Runnable {

A a = new A();

B b = new B();

AvoidDeadlock() {

Thread t = new Thread(this);

t.start();

a.methodA(b); // main thread

}

public void run() {

b.methodB(a); // child thread

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

new AvoidDeadlock();

}

}

2 Use tryLock with Timeout

Use ReentrantLock with tryLock to avoid waiting indefinitely.

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class AvoidDeadlockWithTryLock {

private final Lock lock1 = new ReentrantLock();

private final Lock lock2 = new ReentrantLock();

public void method1() {

try {

if (lock1.tryLock() && lock2.tryLock()) {

// Critical section

}

} finally {

lock1.unlock();

lock2.unlock();

}

}

public void method2() {

try {

if (lock2.tryLock() && lock1.tryLock()) {

// Critical section

}

} finally {

lock2.unlock();

lock1.unlock();

}

}

}

*. How do you check if Thread holds a lock or not in Java.

The Thread class does not provide a direct method to check if a thread holds a lock. However, you can use ReentrantLock to check if the current thread holds the lock.

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class CheckLock {

private final ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void checkLock() {

lock.lock();

try {

// Check if current thread holds the lock

if (lock.isHeldByCurrentThread()) {

System.out.println("Current thread holds the lock");

}

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

CheckLock example = new CheckLock();

example.checkLock();

}

}

*. How do you take Thread dump in Java.

A thread dump provides a snapshot of all the threads running in a JVM. You can take a thread dump in several ways:

1 Using jstack Command

Use the jstack command-line utility to get a thread dump.

jstack <pid>

Replace <pid> with the process ID of your Java application.

2 Using jvisualvm

You can also use the jvisualvm tool, which provides a graphical interface to take a thread dump.

3 Programmatically

You can use ThreadMXBean to take a thread dump programmatically.

import java.lang.management.ManagementFactory;

import java.lang.management.ThreadInfo;

import java.lang.management.ThreadMXBean;

public class ThreadDump {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ThreadMXBean threadMxBean = ManagementFactory.getThreadMXBean();

ThreadInfo[] threadInfos = threadMxBean.dumpAllThreads(true, true);

for (ThreadInfo threadInfo : threadInfos) {

System.out.println(threadInfo.toString());

}

}

}

*. Which JVM parameter is used to control stack size of a Thread.

You can control the stack size of a thread using the -Xss JVM parameter.

java -Xss512k MyClass

This sets the stack size of each thread to 512 kilobytes.

*. ReentrantLock vs Synchronized Keyword In Java.

Synchronized Keyword

- Implicit lock mechanism.

- Block-structured: lock is acquired and released automatically.

- Simpler to use.

- No explicit timeout.

public class SynchronizedExample {

public synchronized void syncMethod() {

// Critical section

}

}

ReentrantLock

- Explicit lock mechanism.

- More flexible: allows explicit lock and unlock, as well as tryLock with timeout.

- Can be fair (first-come, first-served).

- Supports multiple conditions.

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class ReentrantLockExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void lockMethod() {

lock.lock();

try {

// Critical section

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

}

*. Can we run a thread twice in Java?

- Yes, when you call the run() method, it doesn’t create a new thread. The run() method is treated as a normal method and pushed into the main stack, so the main thread would execute it. So, it’s not multi-threading.

*. Can we start a thread twice in Java?

- No, Thread can only start once. If you try to start it for a second time, it will throw an exception, i.e.,

java.lang.IllegalThreadStateException.

*. Next vs hasNext in Java.

-

hasNext() : hasNext() method returns true if iterator have more elements.

-

next() : next() method returns the next element and also moves cursor pointer to the next element.

*. Can you use this() and super() both in a constructor?

- Both this() and super() can not be used together in constructor.

super()- calls the base class constructor whereas

this()- calls current class constructor.

-

Both this() and super() are constructor calls.

-

Constructor call must always be the first statement. So you either have super() or this() as first statement.

*. Can you make a constructor final, static or abstract?

When you set a method as final it means: “I don’t want any class override it.” But according to the Java Language Specification: JLS 8.8 - “Constructor declarations are not members. They are never inherited and therefore are not subject to hiding or overriding.”

When you set a method as static it means: “This method belongs to the class, not a particular object.” But the constructor is implicitly called to initialize an object, so there is no purpose in having a static constructor.

When you set a method as abstract it means: “This method doesn’t have a body and it should be implemented in a child class.” But the constructor is called implicitly when the new keyword is used so it can’t lack a body.

Constructors aren’t inherited so can’t be overridden so no use to have final constructor

Constructor is called automatically when an instance of the class is created, it has access to instance fields of the class. so no use to have static constructor.

Constructor can’t be overridden so no use to have an abstract constructor.

Let’s go through each question and provide a Java code snippet where appropriate to illustrate the concepts.

*. Discuss the pros and cons of using the ThreadLocal class in Java for managing thread-local variables.

Pros:

- Thread Safety: Each thread has its own isolated copy of a ThreadLocal variable, eliminating the need for synchronization.

- Encapsulation: Useful for managing per-thread data such as user sessions or transaction contexts.

- Performance: Reduces the contention between threads since no sharing of variables occurs.

Cons:

- Memory Leaks: Can lead to memory leaks if not managed properly, especially in the case of thread pools where threads are reused.

- Complexity: May add to the complexity of the codebase and make it harder to reason about the flow of data.

- Debugging Difficulty: Debugging thread-local variables can be challenging due to their isolated nature.

Java Code Snippet:

public class ThreadLocalExample {

private static final ThreadLocal<Integer> threadLocal = ThreadLocal.withInitial(() -> 1);

public static void main(String[] args) {

Runnable task = () -> {

int value = threadLocal.get();

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " initial value: " + value);

threadLocal.set(value + 1);

System.out.println(Thread.currentThread().getName() + " updated value: " + threadLocal.get());

};

Thread thread1 = new Thread(task);

Thread thread2 = new Thread(task);

thread1.start();

thread2.start();

}

}

*. What are CompletableFutures in Java, and how do they enable asynchronous programming?

CompletableFuture is part of the Java java.util.concurrent package and provides a way to handle asynchronous programming. It represents a future result of an asynchronous computation and provides methods to handle the result once it’s available, chain multiple computations, and handle errors.

Java Code Snippet:

import java.util.concurrent.CompletableFuture;

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutionException;

public class CompletableFutureExample {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException {

CompletableFuture<String> future = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

// Simulate a long-running task

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new IllegalStateException(e);

}

return "Hello, World!";

});

// Attach a callback to be executed when the future is completed

future.thenAccept(result -> {

System.out.println("Result: " + result);

});

// Wait for the future to complete

future.get();

}

}

*. What do you mean by the statement- Stream is lazy?

Streams in Java are lazy because they do not process data until a terminal operation is invoked. Intermediate operations (like map, filter, etc.) are only executed when a terminal operation (like collect, forEach, etc.) is called.

Java Code Snippet:

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class StreamLazinessExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> names = Arrays.asList("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie");

// Intermediate operations are not executed yet

names.stream()

.filter(name -> {

System.out.println("Filtering: " + name);

return name.startsWith("A");

})

.map(name -> {

System.out.println("Mapping: " + name);

return name.toUpperCase();

});

System.out.println("No terminal operation yet.");

// Terminal operation triggers processing

names.stream()

.filter(name -> {

System.out.println("Filtering: " + name);

return name.startsWith("A");

})

.map(name -> {

System.out.println("Mapping: " + name);

return name.toUpperCase();

})

.forEach(name -> System.out.println("Final Result: " + name));

}

}

*. What does the peek() method do? When should you use it?

The peek() method in Java Streams is an intermediate operation that allows you to perform a side-effect action (such as logging) on each element as it is processed. It is primarily used for debugging purposes to see the contents of the stream at various points.

Java Code Snippet:

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class StreamPeekExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> names = Arrays.asList("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie");

names.stream()

.filter(name -> name.startsWith("A"))

.peek(name -> System.out.println("Filtered: " + name))

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.peek(name -> System.out.println("Mapped: " + name))

.forEach(name -> System.out.println("Final Result: " + name));

}

}

When to use peek():

- Use

peek()when you want to inspect the elements of the stream at a certain point in the pipeline, usually for debugging purposes. - Avoid using

peek()for anything that alters the state or relies on side-effects as it goes against the functional programming paradigm.

*. Java Collections automatic reallocation(ensureCapacity) details when size is reached

1. ArrayList

- Initial Capacity: By default, the initial capacity of an

ArrayListis 10. - Resize Behavior: When an

ArrayListneeds to grow, it increases its size by approximately 50%. - Example: If the current capacity is

n, it will be increased ton + (n >> 1)(which is equivalent to 1.5 times the current capacity).

2. HashMap

- Initial Capacity: The default initial capacity of a

HashMapis 16. - Resize Behavior: When a

HashMapis resized, its capacity is doubled. - Load Factor: The default load factor is 0.75, meaning the

HashMapwill resize when the number of entries exceeds 75% of the current capacity. - Example: If the current capacity is

n, it will be increased to2 * n.

3. HashSet

- Initial Capacity: The default initial capacity of a

HashSetis 16. - Resize Behavior: Similar to

HashMap, aHashSetdoubles its capacity when it exceeds the load factor threshold. - Load Factor: The default load factor is also 0.75.

- Example: If the current capacity is

n, it will be increased to2 * n.

4. LinkedList

LinkedListdoes not have a predefined capacity or resizing mechanism as it is a doubly linked list. It grows dynamically with each addition.

5. Vector

- Initial Capacity: By default, the initial capacity of a

Vectoris 10. - Resize Behavior: When a

Vectorneeds to grow, it doubles its size by default. - Example: If the current capacity is

n, it will be increased to2 * n.

6. Stack

StackextendsVectorand hence inherits its resizing behavior.

7. TreeMap and TreeSet

- These collections are based on Red-Black Trees and do not require resizing because they do not use an underlying array structure. Their growth depends on the tree node insertions and balancing operations.

Summary Table

| Collection Type | Initial Capacity | Resize Increase Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| ArrayList | 10 | 50% |

| HashMap | 16 | 100% |

| HashSet | 16 | 100% |

| LinkedList | Dynamic | N/A |

| Vector | 10 | 100% |

| Stack | 10 | 100% |

| TreeMap | N/A | N/A |

| TreeSet | N/A | N/A |

Note: The actual resizing behavior can be influenced by custom constructors or initial capacity settings provided during instantiation.

| Collection Type | Default Load Factor | Resize Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| ArrayList | N/A | 50% (1.5x) |

| HashMap | 0.75 | 100% (2x) |

| HashSet | 0.75 | 100% (2x) |

| LinkedList | N/A | N/A |

| Vector | N/A | 100% (2x) |

| Stack | N/A | 100% (2x) |

| TreeMap | N/A | N/A |

| TreeSet | N/A | N/A |

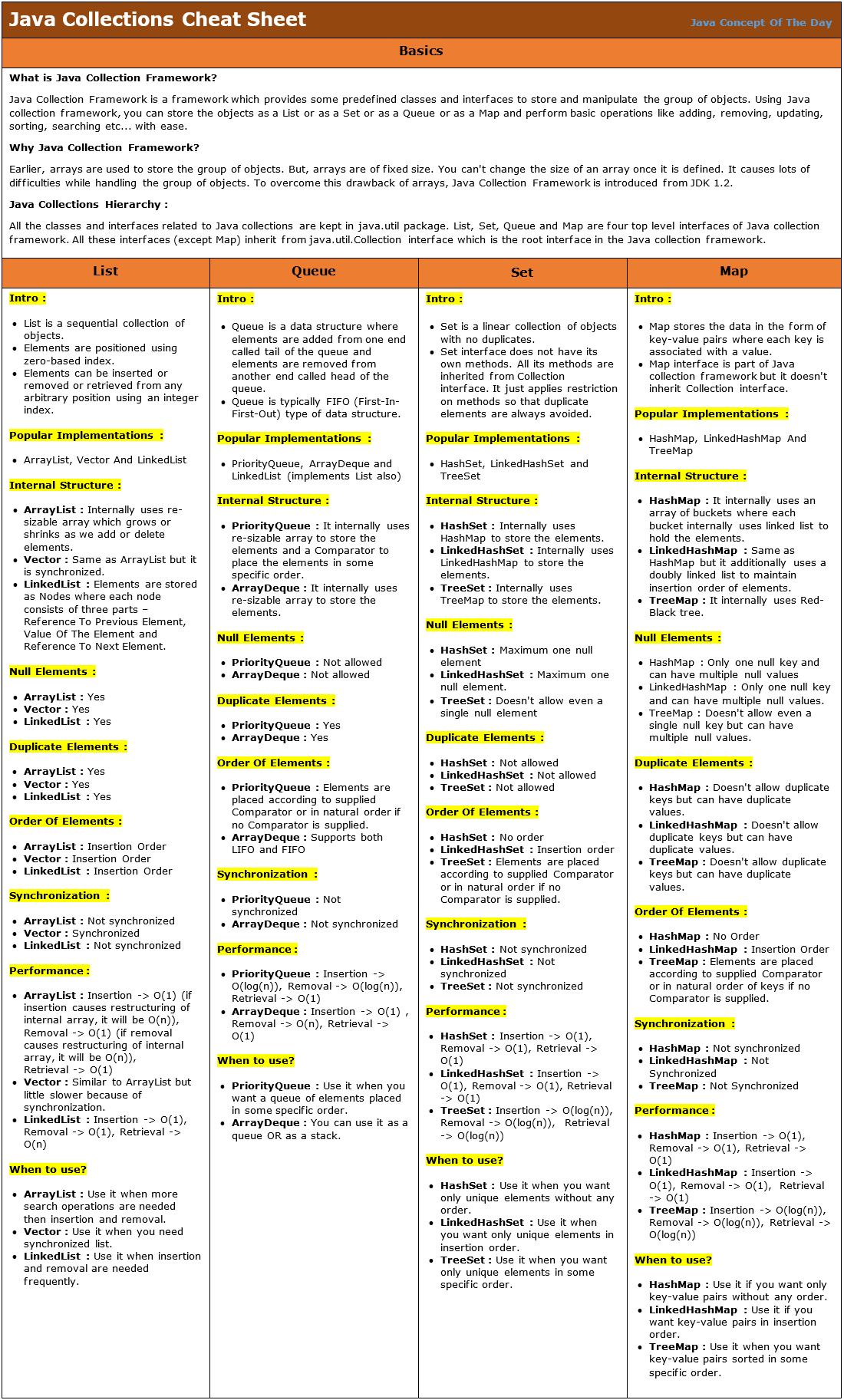

*. Java collections interface and class mindmap

*. Explain Optional class and Functional interface

Java Optional Class

The Optional class in Java, introduced in Java 8, is a container that may or may not hold a non-null value. It is used to represent the presence or absence of a value and to avoid NullPointerException. Optional is often used to handle null values in a more explicit and readable way.

Common Methods of Optional

-

Creation

Optional.of(value): Creates anOptionalwith the given non-null value.Optional.ofNullable(value): Creates anOptionalthat can hold a null value.Optional.empty(): Creates an emptyOptional.

-

Checking Value Presence

isPresent(): Returnstrueif the value is present,falseotherwise.ifPresent(Consumer<? super T> action): Executes the given action if a value is present.

-

Retrieving the Value

get(): Returns the value if present; otherwise, throwsNoSuchElementException.orElse(T other): Returns the value if present; otherwise, returns the provided default value.orElseGet(Supplier<? extends T> other): Returns the value if present; otherwise, invokes the provided supplier and returns the result.orElseThrow(Supplier<? extends X> exceptionSupplier): Returns the value if present; otherwise, throws an exception created by the provided supplier.

-

Transforming the Value

map(Function<? super T, ? extends U> mapper): Applies the provided function to the value if present and returns anOptionalwith the result.flatMap(Function<? super T, Optional<U>> mapper): Applies the provided function to the value if present and returns the result.

Example Usage

import java.util.Optional;

public class OptionalExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creating Optional objects

Optional<String> optionalValue = Optional.of("Hello, World!");

Optional<String> emptyOptional = Optional.empty();

Optional<String> nullableOptional = Optional.ofNullable(null);

// Checking value presence

if (optionalValue.isPresent()) {

System.out.println(optionalValue.get());

}

// Using ifPresent to avoid null checks

optionalValue.ifPresent(System.out::println);

// Providing a default value

System.out.println(nullableOptional.orElse("Default Value"));

// Throwing an exception if value is not present

try {

emptyOptional.orElseThrow(() -> new IllegalStateException("Value is missing!"));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

}

// Transforming the value

Optional<Integer> length = optionalValue.map(String::length);

length.ifPresent(System.out::println);

}

}

Functional Interfaces

Functional interfaces are interfaces with a single abstract method. They provide target types for lambda expressions and method references. Java 8 introduced several built-in functional interfaces in the java.util.function package.

Common Functional Interfaces

-

**Consumer

**: Represents an operation that takes a single input argument and returns no result. - Method:

void accept(T t)

- Method:

-

**Supplier

**: Represents a supplier of results. - Method:

T get()

- Method:

-

Function<T, R>: Represents a function that takes one argument and produces a result.

- Method:

R apply(T t)

- Method:

-

**Predicate

**: Represents a predicate (boolean-valued function) of one argument. - Method:

boolean test(T t)

- Method:

-

**UnaryOperator

**: Represents an operation on a single operand that produces a result of the same type as its operand. - Method:

T apply(T t)

- Method:

-

**BinaryOperator

**: Represents an operation upon two operands of the same type, producing a result of the same type as the operands. - Method:

T apply(T t1, T t2)

- Method:

Example Usage

import java.util.function.*;

public class FunctionalInterfaceExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Using a Consumer

Consumer<String> consumer = System.out::println;

consumer.accept("Hello, Consumer!");

// Using a Supplier

Supplier<String> supplier = () -> "Hello, Supplier!";

System.out.println(supplier.get());

// Using a Function

Function<String, Integer> function = String::length;

System.out.println(function.apply("Hello, Function!"));

// Using a Predicate

Predicate<String> predicate = s -> s.isEmpty();

System.out.println(predicate.test("Hello, Predicate!"));

// Using a UnaryOperator

UnaryOperator<String> unaryOperator = s -> s.toUpperCase();

System.out.println(unaryOperator.apply("Hello, UnaryOperator!"));

// Using a BinaryOperator

BinaryOperator<String> binaryOperator = (s1, s2) -> s1 + s2;

System.out.println(binaryOperator.apply("Hello, ", "BinaryOperator!"));

}

}

Use Case: Combining Optional and Functional Interfaces

A practical use case of combining Optional with functional interfaces is in streamlining operations that might return null values. For example, fetching a user’s email address and then sending a welcome email if the address is present:

import java.util.Optional;

import java.util.function.Consumer;

public class OptionalWithFunctionalInterface {

public static void main(String[] args) {

User user = new User("john.doe@example.com");

sendWelcomeEmail(user);

}

static void sendWelcomeEmail(User user) {

Optional.ofNullable(user.getEmail())

.ifPresent(sendEmail);

}

static Consumer<String> sendEmail = email -> {

// Simulate sending email

System.out.println("Sending welcome email to " + email);

};

static class User {

private String email;

User(String email) {

this.email = email;

}

public String getEmail() {

return email;

}

}

}

*. Use case of Functional interface

Using a functional interface instead of a normal interface in Java has several advantages, particularly in the context of functional programming introduced in Java 8. Here are some key reasons why functional interfaces are preferred in many scenarios:

1. Lambda Expressions and Method References

Functional interfaces are designed to be implemented using lambda expressions and method references, which provide a more concise and readable way to express instances of single-method interfaces.

Example

With a normal interface:

interface Printer {

void print(String message);

}

public class NormalInterfaceExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Printer printer = new Printer() {

@Override

public void print(String message) {

System.out.println(message);

}

};

printer.print("Hello, World!");

}

}

With a functional interface:

@FunctionalInterface

interface Printer {

void print(String message);

}

public class FunctionalInterfaceExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Printer printer = message -> System.out.println(message);

printer.print("Hello, World!");

}

}

The functional interface example is more concise and easier to read.

2. Standardization and Reusability

Java 8 introduced a set of standard functional interfaces in the java.util.function package, which are widely used throughout the JDK and third-party libraries. These standard interfaces improve code reusability and interoperability.

Example

Using a Consumer from java.util.function:

import java.util.function.Consumer;

public class ConsumerExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Consumer<String> printer = message -> System.out.println(message);

printer.accept("Hello, World!");

}

}

3. Stream API Integration

Functional interfaces are essential for using the Stream API, which provides a powerful and expressive way to work with collections and other data sources.

Example

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class StreamExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> names = Arrays.asList("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie");

names.stream()

.filter(name -> name.startsWith("A"))

.forEach(System.out::println);

}

}

In this example, filter and forEach use functional interfaces Predicate and Consumer, respectively.

4. Simplified Syntax

Functional interfaces enable simplified syntax for implementing methods, especially when the implementation is straightforward.

Example

Without lambda (using anonymous inner class):

Runnable runnable = new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

System.out.println("Running");

}

};

new Thread(runnable).start();

With lambda:

Runnable runnable = () -> System.out.println("Running");

new Thread(runnable).start();

5. Improved Code Readability and Maintainability

The use of lambda expressions and functional interfaces often results in code that is more readable and maintainable by reducing boilerplate code and making the intent clearer.

*. Different ways to create an object in Java

-

Using the

newKeyword:MyClass obj = new MyClass();This is the most common way to create an object. It allocates memory for the new object and initializes it by calling the constructor.

-

Using Class.forName() Method:

MyClass obj = (MyClass) Class.forName("com.example.MyClass").newInstance();This method is useful when you need to create an instance of a class dynamically at runtime. It requires handling

ClassNotFoundException,InstantiationException, andIllegalAccessException. -

Using Clone Method:

MyClass obj1 = new MyClass(); MyClass obj2 = (MyClass) obj1.clone();This requires the class to implement the

Cloneableinterface and override theclone()method. It creates a copy of an existing object. -

Using Deserialization:

ObjectInputStream in = new ObjectInputStream(new FileInputStream("file.ser")); MyClass obj = (MyClass) in.readObject();This method is used to create an object from its serialized form. It requires the class to implement the

Serializableinterface. -

Using Factory Methods:

MyClass obj = MyClass.createInstance();A factory method is a static method that returns an instance of the class. It can encapsulate the logic of instance creation and provide flexibility.

-

Using Builder Pattern:

MyClass obj = new MyClass.Builder().setProperty1(value1).setProperty2(value2).build();The Builder pattern is useful for creating complex objects step by step and provides better readability and control over the object creation process.

-

Using Dependency Injection:

@Inject MyClass obj;Dependency Injection (DI) frameworks like Spring or Google Guice can manage object creation and dependency resolution. Objects are injected into the class by the framework.

-

Using Method Handles (Java 7 and above):

MethodHandles.Lookup lookup = MethodHandles.lookup(); MethodHandle constructor = lookup.findConstructor(MyClass.class, MethodType.methodType(void.class)); MyClass obj = (MyClass) constructor.invoke();Method handles provide a way to invoke methods and constructors dynamically.

-

Using Reflection with Constructor Class:

Constructor<MyClass> constructor = MyClass.class.getConstructor(); MyClass obj = constructor.newInstance();Similar to

Class.forName(), this method uses reflection to invoke the constructor and create an instance. -

Using Lambda Expressions (Java 8 and above):

Supplier<MyClass> supplier = MyClass::new; MyClass obj = supplier.get();A functional interface like

Suppliercan be used to create an instance using a lambda expression or method reference.

*. Difference between Volatile and Transient

In Java, volatile and transient are two keywords with distinct purposes related to the memory management and serialization aspects of the language. Here are the key differences between them:

volatile

-

Purpose:

- The

volatilekeyword is used to indicate that a variable’s value will be modified by different threads.

- The

-

Concurrency Control:

- It ensures that the value of the variable is always read from the main memory, and not from a thread’s local cache, providing visibility guarantees for variables in a concurrent environment.

-

Use Case:

- Typically used for flags or state variables that are shared across multiple threads to ensure visibility of changes.

-

Example:

private volatile boolean flag = false; public void setFlag(boolean flag) { this.flag = flag; } public boolean isFlag() { return flag; } -

Behavior:

- It does not provide atomicity for compound actions. For example, operations like

++(increment) are not atomic even if the variable isvolatile.

- It does not provide atomicity for compound actions. For example, operations like

transient

-

Purpose:

- The

transientkeyword is used in the context of serialization. It indicates that a field should not be serialized when an object is converted to a byte stream.

- The

-

Serialization Control:

- It prevents sensitive information or non-serializable data from being serialized, ensuring that these fields are skipped during the serialization process.

-

Use Case:

- Commonly used for fields like passwords, file handles, or any other sensitive or temporary data that should not be part of the serialized form of an object.

-

Example:

public class User implements Serializable { private String username; private transient String password; public User(String username, String password) { this.username = username; this.password = password; } // getters and setters } -

Behavior:

- When an object is deserialized,

transientfields are initialized to their default values (e.g.,nullfor objects,0for numeric types,falsefor booleans).

- When an object is deserialized,

Summary of Differences

| Feature | volatile |

transient |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Indicate variable modified by multiple threads | Prevent field from being serialized |

| Context | Concurrency | Serialization |

| Effect | Ensures visibility of changes across threads | Excludes field from serialization process |

| Use Case | Flags, state variables shared across threads | Sensitive or temporary data within serialized objects |

| Behavior | Guarantees visibility but not atomicity | Field is initialized to default value upon deserialization |

*. LinkedHashSet vs ConcurrentHashMap

LinkedHashSet and ConcurrentHashMap are two distinct classes in Java Collections Framework that serve different purposes and have different characteristics. Here’s a detailed comparison between them:

LinkedHashSet

-

Definition:

LinkedHashSetis a hash table and linked list implementation of theSetinterface. It maintains a doubly-linked list running through all its entries, thus preserving the insertion order.

-

Order:

- It maintains the insertion order of elements, meaning the order in which elements are inserted into the set is the order in which they are iterated.

-

Synchronization:

LinkedHashSetis not synchronized. If multiple threads access aLinkedHashSetconcurrently and at least one of the threads modifies the set, it must be externally synchronized.

-

Performance:

LinkedHashSetprovides constant time performance for basic operations likeadd,remove, andcontains, assuming the hash function disperses elements properly among the buckets.

-

Usage:

- It is used when you need a collection that does not allow duplicates and also preserves the insertion order.

-

Example:

Set<String> linkedHashSet = new LinkedHashSet<>(); linkedHashSet.add("A"); linkedHashSet.add("B"); linkedHashSet.add("C");

ConcurrentHashMap

-

Definition:

ConcurrentHashMapis a thread-safe implementation of theMapinterface. It allows concurrent access to its elements, meaning multiple threads can read and write concurrently without causing inconsistencies.

-

Order:

- It does not maintain any order of its elements. The iteration order is not predictable.

-

Synchronization:

- It is designed for concurrent access and uses a sophisticated locking mechanism (based on segments in earlier versions and internal locks in newer versions) to ensure thread safety without locking the entire map. This allows for high levels of concurrency.

-

Performance:

- It provides efficient concurrent operations. Read operations do not generally block, and write operations lock only the affected part of the map, allowing higher throughput in concurrent environments.

-

Usage:

- It is used when a highly concurrent map is needed. It is particularly useful in multi-threaded applications where read and write operations happen frequently and concurrently.

-

Example:

Map<String, Integer> concurrentHashMap = new ConcurrentHashMap<>(); concurrentHashMap.put("A", 1); concurrentHashMap.put("B", 2); concurrentHashMap.put("C", 3);

Summary of Differences

| Feature | LinkedHashSet |

ConcurrentHashMap |

|---|---|---|

| Data Structure | Hash table with a linked list | Hash table |

| Order | Maintains insertion order | Does not maintain any order |

| Duplicates | Does not allow duplicates | Keys must be unique, values can be duplicate |

| Thread Safety | Not synchronized (requires external synchronization) | Thread-safe (designed for concurrent access) |

| Performance | Constant time for basic operations | Efficient concurrent operations with high throughput |

| Usage | When a set with insertion order is needed | When a thread-safe map with high concurrency is needed |

Choosing Between Them

- Use

LinkedHashSetwhen you need a collection that does not allow duplicates and preserves the insertion order. - Use

ConcurrentHashMapwhen you need a thread-safe map that can handle high levels of concurrency efficiently.

*. Explain fail fast and fail safe iterators

In Java, iterators can be categorized into two types based on their behavior when the underlying collection is modified during iteration: fail-fast and fail-safe iterators. Understanding the difference between these two types of iterators is crucial for developing robust concurrent applications. Here’s a detailed explanation:

Fail-Fast Iterator

-

Definition:

- Fail-fast iterators immediately throw a

ConcurrentModificationExceptionif they detect any structural modification (addition, removal, or update) to the collection while iterating, except through the iterator’s own methods.

- Fail-fast iterators immediately throw a

-

Collections:

- Fail-fast iterators are used by most of the collections in the

java.utilpackage, such asArrayList,HashSet, andHashMap.

- Fail-fast iterators are used by most of the collections in the

-

Mechanism:

- These iterators typically use a modification count (modCount) to keep track of the number of structural modifications. When the iterator is created, it captures the current modCount. On each iteration, it checks if the modCount is the same. If it detects any modification, it throws a

ConcurrentModificationException.

- These iterators typically use a modification count (modCount) to keep track of the number of structural modifications. When the iterator is created, it captures the current modCount. On each iteration, it checks if the modCount is the same. If it detects any modification, it throws a

-

Usage:

- They are useful in detecting bugs where concurrent modification of a collection might occur, providing immediate feedback during development.

-

Example:

List<String> list = new ArrayList<>(); list.add("A"); list.add("B"); list.add("C"); Iterator<String> iterator = list.iterator(); while (iterator.hasNext()) { System.out.println(iterator.next()); list.add("D"); // This line will throw ConcurrentModificationException } -

Drawback:

- Fail-fast behavior does not guarantee that exceptions will be thrown in concurrent environments. It is primarily a best-effort mechanism to detect concurrent modification issues.

Fail-Safe Iterator

-

Definition:

- Fail-safe iterators do not throw

ConcurrentModificationExceptionif the collection is modified during iteration. Instead, they work on a clone of the collection’s data, ensuring safe iteration.

- Fail-safe iterators do not throw

-

Collections:

- Fail-safe iterators are used by collections in the

java.util.concurrentpackage, such asConcurrentHashMap,CopyOnWriteArrayList, andCopyOnWriteArraySet.

- Fail-safe iterators are used by collections in the

-

Mechanism:

- These iterators typically iterate over a snapshot of the collection’s state at the time the iterator was created. For example,

ConcurrentHashMapiterators use the internal data structures that are thread-safe and updated in a way that does not interfere with iteration.

- These iterators typically iterate over a snapshot of the collection’s state at the time the iterator was created. For example,

-

Usage:

- They are useful in concurrent applications where it is necessary to modify the collection during iteration without risking exceptions.

-

Example:

ConcurrentHashMap<String, Integer> map = new ConcurrentHashMap<>(); map.put("A", 1); map.put("B", 2); map.put("C", 3); Iterator<String> iterator = map.keySet().iterator(); while (iterator.hasNext()) { System.out.println(iterator.next()); map.put("D", 4); // No ConcurrentModificationException will be thrown } -

Drawback:

- Fail-safe iterators might not reflect the most recent changes to the collection, as they are iterating over a snapshot.

Summary of Differences

| Feature | Fail-Fast Iterator | Fail-Safe Iterator |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Throws ConcurrentModificationException on modification |

Does not throw exceptions, operates on a snapshot |

| Collections | ArrayList, HashSet, HashMap, etc. |

ConcurrentHashMap, CopyOnWriteArrayList, etc. |

| Mechanism | Checks modification count (modCount) | Iterates over a copy or snapshot of the collection |

| Thread Safety | Not thread-safe, requires external synchronization | Thread-safe, designed for concurrent modifications |

| Reflects Changes | Reflects changes immediately | May not reflect the most recent changes |

| Use Case | Single-threaded or manually synchronized environments | Concurrent environments where modifications during iteration are allowed |

Choosing Between Them

- Use fail-fast iterators in single-threaded environments or where you can ensure external synchronization. They help in quickly detecting and debugging concurrent modification issues.

- Use fail-safe iterators in concurrent environments where the collection might be modified during iteration. They provide a more robust solution for multi-threaded applications, although they might not reflect the most up-to-date state of the collection.

*. ConcurrentHashMap vs HashTable

ConcurrentHashMap and Hashtable are both implementations of the Map interface in Java that support thread-safe operations. However, they have different design philosophies and performance characteristics. Here’s a detailed comparison:

Hashtable

-

Definition:

Hashtableis a synchronized implementation of theMapinterface that was part of the original version of Java.

-

Synchronization:

- All methods of

Hashtableare synchronized. This means that only one thread can access a method of aHashtableobject at a time.

- All methods of

-

Concurrency:

- Due to its synchronization mechanism,

Hashtableis less efficient in terms of concurrency. It locks the entire table for most operations, leading to contention and reduced performance in multi-threaded environments.

- Due to its synchronization mechanism,

-

Null Values:

Hashtabledoes not allow null keys or values. Attempting to insert a null key or value will result in aNullPointerException.

-

Iteration:

- Iterators returned by

Hashtable’s methods are fail-fast. If theHashtableis structurally modified at any time after the iterator is created, except through the iterator’s ownremovemethod, the iterator will throw aConcurrentModificationException.

- Iterators returned by

-

Legacy:

Hashtableis considered a legacy class. It is generally recommended to useConcurrentHashMapor other modern concurrent collections instead.

-

Example:

Map<String, Integer> hashtable = new Hashtable<>(); hashtable.put("A", 1); hashtable.put("B", 2);

ConcurrentHashMap

-

Definition:

ConcurrentHashMapis a highly concurrent implementation of theMapinterface, introduced in Java 5 as part of thejava.util.concurrentpackage.

-

Synchronization:

ConcurrentHashMapuses a more sophisticated locking mechanism called lock stripping. It divides the map into segments and locks only the segment being accessed by a thread, allowing greater concurrency and throughput.

-

Concurrency:

- It is designed for concurrent access and provides better performance in multi-threaded environments. Read operations typically do not lock, and write operations lock only the affected segment.

-

Null Values:

- Like

Hashtable,ConcurrentHashMapdoes not allow null keys or values. Attempting to insert null will result in aNullPointerException.

- Like

-

Iteration:

- Iterators returned by

ConcurrentHashMapare fail-safe. They do not throwConcurrentModificationExceptionbecause they operate on a snapshot of the map’s state at the time the iterator was created.

- Iterators returned by

-

Modern Usage:

ConcurrentHashMapis the preferred choice for thread-safe maps in modern Java applications, particularly when high concurrency and performance are required.

-

Example:

Map<String, Integer> concurrentHashMap = new ConcurrentHashMap<>(); concurrentHashMap.put("A", 1); concurrentHashMap.put("B", 2);

Summary of Differences

| Feature | Hashtable |

ConcurrentHashMap |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronization | Synchronized on all methods | Segment-based locking (lock stripping) |

| Concurrency | Low, locks the entire table for operations | High, allows concurrent reads and segmented writes |

| Null Keys/Values | Not allowed | Not allowed |

| Iteration | Fail-fast (throws ConcurrentModificationException) |

Fail-safe (no ConcurrentModificationException) |

| Performance | Generally lower due to full table locks | Generally higher due to fine-grained locking |

| Usage | Legacy, not recommended for new applications | Recommended for concurrent applications |

Choosing Between Them

-

Use

ConcurrentHashMap:- When you need a thread-safe map with high concurrency.

- When you require better performance in a multi-threaded environment.

- For modern Java applications where you want to take advantage of concurrent collections.

-

Avoid using

Hashtablein new applications. It is considered a legacy class, andConcurrentHashMapis a better alternative for almost all use cases that require thread-safe map implementations.

*. Explain StringJoiner Class.

The StringJoiner class in Java is a utility class introduced in Java 8 that provides an easy way to construct a sequence of characters separated by a delimiter. It can also optionally include a prefix and a suffix. This class is particularly useful for building strings from a collection of elements, especially when you want to insert a delimiter between each element.

Key Features of StringJoiner

-

Delimiter:

- The delimiter is a string that separates each element added to the

StringJoiner. For example, a comma (“,”) can be used as a delimiter to create comma-separated values.

- The delimiter is a string that separates each element added to the

-

Prefix and Suffix:

- Optionally, you can specify a prefix and a suffix that will be added to the resulting string. This is useful for enclosing the joined elements within certain characters, such as brackets or parentheses.

-

Mutable:

StringJoineris mutable, meaning you can add elements to it and modify the sequence as needed.

Constructors

-

With Delimiter Only:

public StringJoiner(CharSequence delimiter)- This constructor initializes the

StringJoinerwith a specified delimiter.

- This constructor initializes the

-

With Delimiter, Prefix, and Suffix:

public StringJoiner(CharSequence delimiter, CharSequence prefix, CharSequence suffix)- This constructor initializes the

StringJoinerwith a specified delimiter, prefix, and suffix.

- This constructor initializes the

Methods

-

add(CharSequence newElement):

- Adds a new element to the

StringJoiner.

- Adds a new element to the

-

length():

- Returns the length of the current sequence of characters.

-

setEmptyValue(CharSequence emptyValue):

- Sets the sequence of characters to be used when no elements have been added.

-

merge(StringJoiner other):

- Merges the contents of another

StringJoinerinto the current one.

- Merges the contents of another

-

toString():

- Returns the string representation of the

StringJoiner.

- Returns the string representation of the

Examples

Example 1: Basic Usage with Delimiter

import java.util.StringJoiner;

public class StringJoinerExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

StringJoiner joiner = new StringJoiner(", ");

joiner.add("Apple");

joiner.add("Banana");

joiner.add("Cherry");

System.out.println(joiner.toString()); // Output: Apple, Banana, Cherry

}

}

Example 2: Usage with Delimiter, Prefix, and Suffix

import java.util.StringJoiner;

public class StringJoinerExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

StringJoiner joiner = new StringJoiner(", ", "[", "]");

joiner.add("Apple");

joiner.add("Banana");

joiner.add("Cherry");

System.out.println(joiner.toString()); // Output: [Apple, Banana, Cherry]

}

}

Example 3: Setting an Empty Value

import java.util.StringJoiner;

public class StringJoinerExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

StringJoiner joiner = new StringJoiner(", ");

joiner.setEmptyValue("No fruits");

System.out.println(joiner.toString()); // Output: No fruits

joiner.add("Apple");

joiner.add("Banana");

System.out.println(joiner.toString()); // Output: Apple, Banana

}

}

Use Cases

- Building CSV Strings:

StringJoineris perfect for creating comma-separated values from a list of elements. - Joining Collection Elements: It can be used to join elements of a collection with a specified delimiter.

- Creating Readable Output: When you need to construct a string that includes delimiters, prefixes, and suffixes in a readable format.

*. Explain Metaspace.

In Java 11, the Metaspace is a memory space that replaces the Permanent Generation (PermGen) from earlier versions of Java. It is part of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) and is used to store metadata about the classes that the JVM loads. Here’s an in-depth look at Metaspace:

What is Metaspace?

-

Definition:

- Metaspace is a native memory region used by the JVM to store class metadata, such as class definitions, method definitions, and other reflective data.

-

Replacement for PermGen:

- Prior to Java 8, class metadata was stored in the PermGen space, which was part of the heap memory. Metaspace, introduced in Java 8, replaces PermGen and moves class metadata storage to native memory.

Key Features of Metaspace

-

Native Memory:

- Unlike PermGen, which was part of the heap, Metaspace uses native memory (outside the JVM heap). This means it is not subject to the same garbage collection mechanisms as the heap memory.

-

Automatic Management:

- Metaspace automatically increases its size as needed, subject to limits that can be configured, making it more flexible than PermGen, which had a fixed size and could cause

OutOfMemoryErrorif it was exhausted.

- Metaspace automatically increases its size as needed, subject to limits that can be configured, making it more flexible than PermGen, which had a fixed size and could cause

-

Configuration Parameters:

- Metaspace size and behavior can be controlled using JVM parameters:

-XX:MetaspaceSize: Initial size of Metaspace.-XX:MaxMetaspaceSize: Maximum size of Metaspace. If not set, Metaspace can grow until the native memory is exhausted.-XX:MinMetaspaceFreeRatioand-XX:MaxMetaspaceFreeRatio: These parameters control the space available for class metadata allocation before and after garbage collection.

- Metaspace size and behavior can be controlled using JVM parameters:

-

Garbage Collection:

- Class metadata stored in Metaspace is subject to garbage collection. When classes are no longer used, their metadata can be reclaimed.

-

Improved Performance and Stability:

- The move to native memory helps in improving performance and stability, as it allows better handling of class metadata and avoids the limitations of PermGen.

Key JVM Parameters for Metaspace

-

-XX:MetaspaceSize:

- Sets the initial (and minimum) size of the Metaspace. Example:

-XX:MetaspaceSize=128M

- Sets the initial (and minimum) size of the Metaspace. Example:

-

-XX:MaxMetaspaceSize:

- Sets the maximum size of the Metaspace. Example:

-XX:MaxMetaspaceSize=512M

- Sets the maximum size of the Metaspace. Example:

-

-XX:MinMetaspaceFreeRatio:

- Sets the minimum percentage of free space to be maintained in the Metaspace after a garbage collection to avoid frequent garbage collections.

-

-XX:MaxMetaspaceFreeRatio:

- Sets the maximum percentage of free space to be maintained in the Metaspace after a garbage collection to avoid over-allocating memory.

Example Usage

java -XX:MetaspaceSize=128M -XX:MaxMetaspaceSize=512M MyApplication

Monitoring Metaspace

You can monitor Metaspace usage using various tools:

-

JVisualVM:

- A visual tool that provides detailed information about the JVM, including Metaspace usage.

-

JConsole:

- A monitoring tool that comes with the JDK, providing insights into various memory spaces, including Metaspace.

-

Garbage Collection Logs:

- Enabling GC logs can provide information about Metaspace usage. For example:

-Xlog:gc*

- Enabling GC logs can provide information about Metaspace usage. For example:

-

jstat:

- The

jstattool can provide real-time statistics about the JVM, including Metaspace.

- The

Why Metaspace?

- Flexibility: By using native memory, Metaspace can grow dynamically, reducing the chances of

OutOfMemoryErrorrelated to class metadata. - Improved GC: Separating class metadata from the heap allows more efficient garbage collection, improving overall application performance.

- Scalability: Applications with a large number of classes benefit from the more scalable memory management provided by Metaspace.

*. Stream API vs Collection API

The Stream API and Collection API in Java are both part of the Java Collections Framework, but they serve different purposes and have different characteristics. Here’s a comparison of the two:

Collection API

The Collection API is part of the Java Collections Framework and provides a way to store and manage groups of objects. Some common types of collections are List, Set, and Map.

Key Characteristics:

- Data Storage: Collections are used to store data.

- Manipulation: They provide methods to add, remove, and update elements.

- Traversal: Collections can be traversed using iterators or for-each loops.

- Mutability: Collections can be modified (add, remove, or update elements).

Examples:

- List: An ordered collection (also known as a sequence). Allows duplicate elements.

List<String> list = new ArrayList<>(); list.add("apple"); list.add("banana"); list.add("apple"); - Set: A collection that does not allow duplicate elements.

Set<String> set = new HashSet<>(); set.add("apple"); set.add("banana"); set.add("apple"); // Duplicate element will not be added - Map: A collection of key-value pairs.

Map<String, Integer> map = new HashMap<>(); map.put("apple", 1); map.put("banana", 2); map.put("apple", 3); // Key "apple" will be updated to 3

Stream API

The Stream API, introduced in Java 8, is used for processing sequences of elements. It allows operations on data in a declarative manner (similar to SQL).

Key Characteristics:

- Processing: Streams are used to process data, such as filtering, mapping, and reducing.

- Pipeline: Streams allow chaining multiple operations into a pipeline.

- Lazy Evaluation: Intermediate operations are lazy; they are not executed until a terminal operation is invoked.

- Functional Programming: Streams encourage a functional programming style using lambda expressions.

- Immutability: Streams do not modify the underlying data structure.

Examples:

- Creating a Stream: Streams can be created from collections, arrays, or I/O channels.

List<String> list = Arrays.asList("apple", "banana", "cherry"); Stream<String> stream = list.stream(); - Intermediate Operations: Operations that transform a stream into another stream. Examples include

filter,map, andsorted.Stream<String> filteredStream = stream.filter(s -> s.startsWith("a")); Stream<String> mappedStream = stream.map(String::toUpperCase); - Terminal Operations: Operations that produce a result or a side-effect. Examples include

collect,forEach, andreduce.List<String> result = stream.filter(s -> s.startsWith("a")) .map(String::toUpperCase) .collect(Collectors.toList());

Comparison Summary

| Feature | Collection API | Stream API |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Data storage and manipulation | Data processing and computation |

| Mutability | Mutable | Immutable |

| Type | Concrete data structures (List, Set, Map) | Abstract processing pipeline |

| Operations | Basic CRUD operations (add, remove, update) | Functional operations (filter, map, reduce) |

| Traversal | Iterators, for-each loops | Internal iteration using functional style |

| Evaluation | Eager (operations executed immediately) | Lazy (operations executed when terminal operation is invoked) |

| Suitability | Direct manipulation of data | Complex data processing pipelines |

Use Cases

-

Collection API:

- Managing and manipulating collections of data.

- Use when you need to frequently add, remove, or update elements in a collection.

-

Stream API:

- Processing large datasets.

- Performing complex operations on data, such as filtering, mapping, and reducing.

- When you want to use a functional programming style to make code more readable and concise.