interviewprep

Title: Java Part 2

Title: Java

Table of Contents

*. What are the key principles of object-oriented programming, and could you provide an example of each?

Object-oriented programming (OOP) in Java is based on four key principles: Encapsulation, Inheritance, Polymorphism, and Abstraction. Here’s an overview of each principle with examples:

1. Encapsulation

Encapsulation is the bundling of data (variables) and methods (functions) that operate on the data into a single unit, usually a class. It restricts direct access to some of the object’s components, which is a means of preventing accidental interference and misuse of the data.

Example:

public class EncapsulationExample {

private String name;

private int age;

// Getter method for name

public String getName() {

return name;

}

// Setter method for name

public void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

// Getter method for age

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

// Setter method for age

public void setAge(int age) {

this.age = age;

}

}

Example of Encapsulation with Validation

While getters and setters are the most common way to achieve encapsulation, another way to demonstrate encapsulation is by restricting direct access to certain class members and providing methods that control access and modify these members in a controlled manner. This can include methods that perform validation or other logic before modifying the state.

BankAccount Class with Encapsulation

public class BankAccount {

// Private fields to encapsulate the data

private String accountNumber;

private double balance;

// Constructor

public BankAccount(String accountNumber, double initialBalance) {

this.accountNumber = accountNumber;

if (initialBalance >= 0) {

this.balance = initialBalance;

} else {

this.balance = 0;

}

}

// Method to deposit money with validation

public void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount;

System.out.println("Deposited: $" + amount);

} else {

System.out.println("Deposit amount must be positive.");

}

}

// Method to withdraw money with validation

public void withdraw(double amount) {

if (amount > 0 && amount <= balance) {

balance -= amount;

System.out.println("Withdrew: $" + amount);

} else {

System.out.println("Invalid withdrawal amount or insufficient balance.");

}

}

// Method to display the current balance

public void displayBalance() {

System.out.println("Current balance: $" + balance);

}

// Private method for internal use

private void logTransaction(String message) {

// Log transaction (hypothetical implementation)

System.out.println("Transaction Log: " + message);

}

}

Main Class to Use BankAccount

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creating a BankAccount object

BankAccount account = new BankAccount("123456789", 1000);

// Accessing the BankAccount through its methods

account.displayBalance(); // Output: Current balance: $1000

account.deposit(500); // Output: Deposited: $500

account.displayBalance(); // Output: Current balance: $1500

account.withdraw(200); // Output: Withdrew: $200

account.displayBalance(); // Output: Current balance: $1300

account.withdraw(2000); // Output: Invalid withdrawal amount or insufficient balance.

}

}

Explanation

-

Private Fields: The

accountNumberandbalancefields are private, meaning they cannot be accessed directly from outside the class. This encapsulates the data, ensuring that it can only be modified through the class methods. -

Constructor with Validation: The constructor ensures that the initial balance cannot be negative.

-

Methods with Validation: The

depositandwithdrawmethods include logic to validate the input. This ensures that the state of theBankAccountobject remains consistent and valid. For example, you can’t withdraw more money than is available in the account, and you can’t deposit or withdraw a negative amount. -

Private Helper Method: The

logTransactionmethod is private, meaning it is intended for internal use within theBankAccountclass only. This method can be used to log transactions without exposing this functionality to the outside world.

By using methods with built-in validation and making fields private, this example demonstrates encapsulation by controlling how the internal state of an object is accessed and modified.

2. Inheritance

Inheritance is a mechanism wherein a new class is derived from an existing class. The new class, known as the subclass (or derived class), inherits the attributes and methods of the superclass (or base class).

Example:

// Superclass

public class Animal {

public void eat() {

System.out.println("This animal eats food.");

}

}

// Subclass

public class Dog extends Animal {

public void bark() {

System.out.println("The dog barks.");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Dog dog = new Dog();

dog.eat(); // Inherited method

dog.bark(); // Own method

}

}

3. Polymorphism

Polymorphism allows methods to do different things based on the object it is acting upon, even though they share the same name. It can be achieved through method overriding (runtime polymorphism) and method overloading (compile-time polymorphism).

Example:

// Method Overloading (Compile-time Polymorphism)

public class PolymorphismExample {

// Method to add two integers

public int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

// Method to add three integers

public int add(int a, int b, int c) {

return a + b + c;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

PolymorphismExample example = new PolymorphismExample();

System.out.println(example.add(2, 3)); // Output: 5

System.out.println(example.add(2, 3, 4)); // Output: 9

}

}

// Method Overriding (Runtime Polymorphism)

public class Animal {

public void sound() {

System.out.println("This animal makes a sound");

}

}

public class Cat extends Animal {

@Override

public void sound() {

System.out.println("The cat meows");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Animal myCat = new Cat();

myCat.sound(); // Output: The cat meows

}

}

4. Abstraction

Abstraction is the concept of hiding the complex implementation details and showing only the essential features of the object. It can be achieved using abstract classes and interfaces.

Example:

// Abstract Class

abstract class Animal {

// Abstract method (does not have a body)

public abstract void animalSound();

// Regular method

public void sleep() {

System.out.println("This animal sleeps.");

}

}

// Subclass (inherited from Animal)

public class Pig extends Animal {

public void animalSound() {

System.out.println("The pig says: wee wee");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Pig myPig = new Pig();

myPig.animalSound(); // Output: The pig says: wee wee

myPig.sleep(); // Output: This animal sleeps.

}

}

Is the @Override Annotation Necessary for Interface Methods?

The @Override annotation is not strictly necessary when implementing methods from an interface, but it is highly recommended. Here’s why:

-

Compile-Time Checking: The

@Overrideannotation tells the compiler that the method is intended to override a method in a superclass or implement an interface method. If the method signature does not match the method in the interface (e.g., due to a typo or incorrect parameters), the compiler will generate an error. This helps catch mistakes early. -

Readability and Maintenance: Using

@Overridemakes the code more readable and maintainable. It clearly indicates that the method is an implementation of an interface method, making it easier for other developers (or your future self) to understand the code.

Example:

public interface Animal {

void animalSound();

void sleep();

}

public class Pig implements Animal {

@Override

public void animalSound() {

System.out.println("The pig says: wee wee");

}

@Override

public void sleep() {

System.out.println("The pig sleeps.");

}

}

Why Can’t We Create Objects of an Interface or Abstract Class?

Interfaces:

- Purpose: An interface is a contract that specifies what methods a class must implement but does not provide any implementation itself.

- Instantiation: Since interfaces do not have any concrete implementation, there is no behavior to instantiate. You cannot create an instance of an interface directly because it does not have any code to execute.

Abstract Classes:

- Purpose: An abstract class can provide both complete (concrete) methods and incomplete (abstract) methods that must be implemented by subclasses.

- Instantiation: Similar to interfaces, you cannot create an instance of an abstract class because it might contain abstract methods with no implementation. Even if it has some concrete methods, it is meant to be a base class to be extended, not to be instantiated on its own.

Example:

// Interface

public interface Animal {

void animalSound();

void sleep();

}

// Abstract Class

public abstract class Bird {

public abstract void fly(); // Abstract method

public void eat() { // Concrete method

System.out.println("The bird eats.");

}

}

// Class implementing an interface

public class Pig implements Animal {

@Override

public void animalSound() {

System.out.println("The pig says: wee wee");

}

@Override

public void sleep() {

System.out.println("The pig sleeps.");

}

}

// Class extending an abstract class

public class Sparrow extends Bird {

@Override

public void fly() {

System.out.println("The sparrow flies.");

}

}

// Main class

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Pig myPig = new Pig(); // Valid

myPig.animalSound();

myPig.sleep();

Sparrow mySparrow = new Sparrow(); // Valid

mySparrow.fly();

mySparrow.eat();

// Animal myAnimal = new Animal(); // Invalid, cannot instantiate interface

// Bird myBird = new Bird(); // Invalid, cannot instantiate abstract class

}

}

default methods and static methods in Interface JAVA 8

In Java 8, interfaces can have concrete methods. These are called default methods and static methods.

Default Methods

Default methods are methods defined in an interface with the default keyword and provide a concrete implementation. This feature allows interfaces to evolve by adding new methods without breaking existing implementations of the interface.

Example of Default Methods:

public interface Animal {

void animalSound(); // Abstract method

// Default method

default void sleep() {

System.out.println("This animal sleeps.");

}

}

public class Pig implements Animal {

@Override

public void animalSound() {

System.out.println("The pig says: wee wee");

}

// Pig class does not need to implement sleep() method

// as it has a default implementation in the interface

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Pig myPig = new Pig();

myPig.animalSound(); // Output: The pig says: wee wee

myPig.sleep(); // Output: This animal sleeps.

}

}

Static Methods

Static methods in interfaces are similar to static methods in classes. They belong to the interface itself rather than to instances of the interface.

Example of Static Methods:

public interface Animal {

void animalSound(); // Abstract method

// Static method

static void printInfo() {

System.out.println("This is an animal.");

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Animal.printInfo(); // Output: This is an animal.

}

}

Why Introduce Default and Static Methods?

- Backward Compatibility: Default methods allow the addition of new methods to interfaces without breaking the existing implementations. Before Java 8, adding a new method to an interface would force all implementing classes to provide an implementation for that method, potentially breaking a lot of code.

- Utility Methods: Static methods in interfaces provide a way to include utility methods related to the interface without requiring a separate utility class.

These principles are fundamental to writing robust, maintainable, and scalable object-oriented code in Java.

*. Is it possible for the ‘public static void main’ method to work without being named ‘main’? If not, why? Describe ‘public static void main’

The main method must be named main because it is a convention specified by the JVM to identify the entry point of a Java application. Deviating from this convention will prevent the JVM from starting the program correctly.

Public:- it is an access specifier that means it will be accessed by publically. Static:- it is access modifier that means when the java program is load then it will create the space in memory automatically. Void:- it is a return type that is it does not return any value. main():- it is a method or a function name.

*. Can we run a class in Java 1.9, which was compiled in Java 1.8?

yes but in some cases it might not work.

*. Can a single Java class contain multiple ‘main’ methods? If so, how does the program determine which one to execute?

Yes, a single Java class can contain multiple main methods with different parameter lists (overloaded), but only the public static void main(String[] args) method will be executed by the JVM.

Below is a code example of a single Java class containing multiple main methods with different parameter lists (overloaded). The JVM will only execute the public static void main(String[] args) method.

public class MainMethodExample {

// Standard main method that JVM will execute

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello from the standard main method!");

// Calling other main methods for demonstration

main(42);

main("Overloaded main method");

}

// Overloaded main method with an integer parameter

public static void main(int arg) {

System.out.println("Hello from the main method with int parameter: " + arg);

}

// Overloaded main method with a string parameter

public static void main(String arg) {

System.out.println("Hello from the main method with String parameter: " + arg);

}

}

Explanation

-

Standard

mainmethod: This is the method that the JVM will look for and execute when the program starts. -

Overloaded

mainmethods: These methods have different parameter lists (one takes anint, and the other takes aString). These will not be executed by the JVM automatically but can be called from within the standardmainmethod or other methods in the class.

Execution

When you run the program using the command java MainMethodExample, the JVM will execute the standard public static void main(String[] args) method, and the output will be:

Hello from the standard main method!

Hello from the main method with int parameter: 42

Hello from the main method with String parameter: Overloaded main method

*. Describe what is constructor and types of constructor in JAVA with code example.

What is a Constructor in Java?

A constructor in Java is a special method that is called when an object is instantiated. The purpose of a constructor is to initialize the newly created object. Constructors have the same name as the class and do not have a return type, not even void.

Types of Constructors in Java

- Default Constructor: A no-argument constructor provided by the compiler if no constructors are defined in the class. It initializes the object with default values.

- No-Argument Constructor: A constructor that does not take any parameters. If a class does not explicitly define a constructor, the compiler automatically provides a default no-argument constructor.

- Parameterized Constructor: A constructor that takes arguments to initialize the object with specific values.

Examples

1. Default Constructor

If you do not provide any constructor, Java provides a default constructor that initializes the object with default values.

public class DefaultConstructorExample {

int value;

// No need to explicitly define a default constructor

// Java provides one if no constructors are defined

public static void main(String[] args) {

DefaultConstructorExample obj = new DefaultConstructorExample();

System.out.println("Value: " + obj.value); // Output: Value: 0

}

}

2. No-Argument Constructor

You can explicitly define a no-argument constructor to initialize default values.

public class NoArgConstructorExample {

int value;

// No-argument constructor

public NoArgConstructorExample() {

value = 42; // Default initialization

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

NoArgConstructorExample obj = new NoArgConstructorExample();

System.out.println("Value: " + obj.value); // Output: Value: 42

}

}

3. Parameterized Constructor

A constructor with parameters allows you to pass initial values to the object at the time of creation.

public class ParameterizedConstructorExample {

int value;

// Parameterized constructor

public ParameterizedConstructorExample(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

ParameterizedConstructorExample obj = new ParameterizedConstructorExample(100);

System.out.println("Value: " + obj.value); // Output: Value: 100

}

}

Summary

- Default Constructor: Provided by the compiler if no constructors are defined.

- No-Argument Constructor: Explicitly defined with no parameters, used to initialize default values.

- Parameterized Constructor: Allows passing specific values to initialize the object during instantiation.

These constructors help in the creation and initialization of objects, providing flexibility in how objects are instantiated and initialized in Java.

*. Explain the differences between encapsulation and abstraction in Java with examples.

Encapsulation and abstraction are both fundamental concepts in object-oriented programming (OOP), and especially in Java. While they are interrelated, they serve distinct purposes:

Encapsulation:

- Focus: Bundling data (attributes) and methods (functions) that operate on that data together within a single unit, typically a class.

- Goal: Data protection and controlled access. Encapsulation ensures data integrity by restricting direct access to attributes and providing controlled access mechanisms through methods (getters and setters).

- Implementation: Achieved using access modifiers (public, private, protected) in Java. Public methods allow external access, while private methods are hidden within the class.

Example:

public class Car {

private String model; // Encapsulated data (attribute)

private int speed; // Encapsulated data (attribute)

public void accelerate() { // Public method (function)

speed++;

}

public int getSpeed() { // Public getter method

return speed;

}

}

In this example, model and speed are private attributes hidden within the Car class. The accelerate method modifies the speed, and the getSpeed method provides controlled access to the value.

Abstraction:

- Focus: Hiding the internal implementation details of an object and exposing only the essential functionalities.

- Goal: Simplifies complex functionalities and promotes loose coupling (reduced reliance between objects). Users interact with the “what” rather than the “how”.

- Implementation: Achieved through interfaces and abstract classes. Interfaces define functionalities (methods) without implementation details. Abstract classes provide partial implementations that can be extended by subclasses.

Example:

public interface Shape {

double calculateArea(); // Abstract method (what)

}

public abstract class Vehicle {

public abstract void start(); // Abstract method (what)

}

public class ElectricCar extends Vehicle {

@Override

public void start() {

// Implementation details (how) for electric car start

}

}

The Shape interface defines the calculateArea method without specifying how to calculate it. Different shapes (classes implementing Shape) can provide their specific implementations. Similarly, the Vehicle class has an abstract start method that gets implemented in subclasses like ElectricCar.

Key Differences:

- Encapsulation focuses on data protection and access control, while abstraction focuses on hiding implementation details and exposing functionalities.

- Encapsulation is typically achieved within a class, while abstraction can be applied across classes using interfaces and inheritance.

By effectively using encapsulation and abstraction, Java programmers can create secure, maintainable, and reusable code.

*. Differentiate between Method Overloading and Method Overriding, providing examples.

Method overloading and overriding are two powerful concepts in Java that deal with methods (functions) within classes. They might seem similar at first glance, but they have distinct purposes and functionalities:

Method Overloading

- Definition: Occurs within the same class when multiple methods share the same name but have different parameter lists (number, type, or both).

- Purpose: Provides flexibility for methods with the same functionality but acting on different data types or quantities. Improves code readability.

- Key Points:

- Same method name within a class.

- Different parameter lists (number or type of parameters).

- Return type can be the same or different.

- Example of compile-time polymorphism (the compiler decides which method to call based on arguments at compile time).

Code Example:

public class Calculator {

public int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

public double add(double a, double b) {

return a + b;

}

public String add(String a, String b) {

return a.concat(b); // String concatenation for combining strings

}

}

In this example, the Calculator class has three add methods. Each takes different parameters (two integers, two doubles, or two strings), allowing for addition of different data types.

Method Overriding

- Definition: Occurs in inheritance hierarchies when a subclass re-implements a method inherited from its superclass.

- Purpose: Provides a way for subclasses to specialize the behavior of inherited methods.

- Key Points:

- Same method name and parameter list (signature) in subclass and superclass.

- Must follow inheritance relationship (subclass overrides superclass method).

- Return type must be the same or a subtype (covariant) of the superclass return type.

- Example of run-time polymorphism (the actual method called is determined at runtime based on the object’s type).

public class Animal {

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Generic animal sound");

}

}

public class Dog extends Animal {

@Override // Optional annotation indicating overriding

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Woof!");

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Animal myAnimal = new Animal(); // Create an Animal object

myAnimal.makeSound(); // Calls Animal's makeSound

Dog myDog = new Dog(); // Create a Dog object

myDog.makeSound(); // Calls Dog's overridden makeSound

}

}

Here, the Animal class has a makeSound method. The Dog class inherits from Animal and overrides the makeSound method to provide a specific sound for dogs.

You would use Animal an = new Dog(); in Java when you want to leverage inheritance and polymorphism for code flexibility and reusability. Here’s a breakdown of the scenario:

Inheritance:

- The

Dogclass likely inherits from theAnimalclass. This meansDoginherits attributes and methods fromAnimal.

Polymorphism:

- By creating a reference variable

anof typeAnimaland assigning a newDogobject to it, you are taking advantage of polymorphism. - An object reference variable can hold a reference to objects of its own class or subclasses. In this case,

Animalis the superclass, andDogis the subclass.

Use Cases:

There are several reasons why you might use this approach:

-

Collections: If you have a collection (like an array or list) that needs to store objects of various animal types (dogs, cats, birds, etc.), all of which inherit from a common

Animalclass. You can useAnimalas the reference type for the collection elements, allowing you to store objects of different subclasses (likeDog). -

Generic Functionality: If you want to focus on common functionalities shared by all animals (e.g., making a sound, eating), you can define these methods in the

Animalclass. Then, subclasses likeDogcan override them to provide specific implementations. Using theAnimalreference variablean, you can call these methods, and the appropriate version (fromAnimalor the subclass likeDog) will be executed based on the actual object type at runtime (polymorphism).

Example:

public class Animal {

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Generic animal sound");

}

}

public class Dog extends Animal {

@Override

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Woof!");

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Animal an = new Dog(); // Create a Dog object but assign it to an Animal reference

an.makeSound(); // Calls Dog's overridden makeSound (due to polymorphism)

}

}

Important Caveats:

- While

ancan call methods defined in theAnimalclass, it cannot directly access methods specific toDogunless you cast it back to aDogobject (but that might defeat the purpose of usingAnimalas the reference type). - If you only need the functionalities of a

Dogand don’t care about treating it as a generic animal, it’s generally better to directly useDogfor the reference variable and object creation.

In Summary:

- Method overloading deals with multiple methods with the same name but different functionalities within a class.

- Method overriding deals with subclasses providing their specific implementations for inherited methods.

*. Explain Inheritance vs Composition

Inheritance and composition are fundamental concepts in object-oriented programming (OOP) used to establish relationships between classes in Java. They both achieve code reusability, but in different ways:

Inheritance (IS-A Relationship):

- Represents a hierarchical relationship between classes.

- A subclass (“child”) inherits attributes and methods from its superclass (“parent”).

- Subclasses can add new attributes and methods or override inherited ones to specialize behavior.

Java Code Example:

public class Animal {

private String name;

private int age;

public Animal(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Generic animal sound");

}

}

public class Dog extends Animal {

private String breed;

public Dog(String name, int age, String breed) {

super(name, age); // Call superclass constructor

this.breed = breed;

}

@Override

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Woof!");

}

}

In this example, Dog inherits from Animal. Dog has its own attribute breed and overrides the makeSound method to provide a specific sound for dogs.

Composition (HAS-A Relationship):

- Represents a “has-a” relationship between objects.

- A class contains an instance of another class as a member variable.

- The containing class can access the member object’s methods and attributes.

- Subclasses are not involved.

Java Code Example:

public class Engine {

private int horsePower;

public Engine(int horsePower) {

this.horsePower = horsePower;

}

public void start() {

System.out.println("Engine started!");

}

}

public class Car {

private String model;

private Engine engine; // Car HAS-A Engine

public Car(String model, Engine engine) {

this.model = model;

this.engine = engine;

}

public void accelerate() {

engine.start(); // Access Engine's method through the member object

System.out.println(model + " is accelerating!");

}

}

Here, Car does not inherit from Engine. Instead, Car has an Engine object as a member variable. Car can access the Engine’s methods (like start) to perform actions related to the engine.

Key Differences:

- Relationship: Inheritance represents an “is-a” relationship, while composition represents a “has-a” relationship.

- Code Reusability: Inheritance allows for code reuse through inheritance hierarchy. Composition allows for code reuse by creating objects of other classes and using their functionalities.

- Flexibility: Inheritance creates a tighter coupling between classes. Composition provides more flexibility as different objects can be used in the containing class.

- Multiple Inheritance: Java doesn’t support direct multiple inheritance (a class inheriting from multiple superclasses). Composition allows for a kind of simulated multiple inheritance by having a class contain objects of multiple other classes.

Choosing Between Inheritance and Composition:

- Use inheritance when there’s a true “is-a” relationship and the subclass specializes the behavior of the superclass.

- Use composition for a more flexible approach where one object needs to utilize the functionalities of another without a strict inheritance hierarchy.

*. What are access modifiers in Java, and which ones are inherited by subclasses?

Access modifiers in Java are keywords that define the accessibility (visibility) of classes, fields (attributes), methods, and constructors. They control which parts of your code can access these elements. There are four main access modifiers:

- Public: Members declared as

publicare accessible from anywhere in your program, regardless of the package or class. - Private: Members declared as

privateare only accessible within the class they are defined in. They are hidden from other classes. - Protected: Members declared as

protectedare accessible from within the class they are defined in, as well as from subclasses (regardless of package). - Default (Package-Private): If no access modifier is explicitly declared, the member is considered package-private. This means it’s accessible from within the same package but hidden from outside the package.

Inheritance and Access Modifiers:

- Public and Protected Members: These are inherited by subclasses. Subclasses can access and potentially override them.

- Private Members: These are not inherited by subclasses. They are strictly confined to the class where they are defined.

- Default (Package-Private) Members: These are generally not inherited by subclasses from different packages. However, subclasses within the same package can access them.

Here’s a table summarizing access modifiers and inheritance:

| Access Modifier | Accessible By | Inherited By Subclasses? |

|---|---|---|

| Public | Everywhere | Yes |

| Private | Within the class only | No |

| Protected | Within the class, subclasses (regardless of package) | Yes |

| Default (Package-Private) | Within the same package | No (unless subclass is in the same package) |

Example:

public class Animal {

private String name; // Only accessible within Animal

protected int age; // Accessible in Animal and subclasses

public void makeSound() { // Accessible from anywhere

System.out.println("Generic animal sound");

}

}

public class Dog extends Animal {

public String breed; // Accessible from anywhere

@Override

public void makeSound() {

System.out.println("Woof!");

}

}

In this example:

name(private) is only accessible withinAnimal.age(protected) is accessible in bothAnimalandDog.makeSound(public) inAnimaland the overridden version inDogare accessible from anywhere.breed(public) inDogis accessible from anywhere.

Key Points:

- Use access modifiers judiciously to control access and promote encapsulation.

- Protected members are useful for creating a base class with core functionalities that can be extended by subclasses.

- Private members ensure data protection and prevent unintended modifications.

*. Default vs protected access specifiers.

Default: Visible within the package, not inherited by subclasses. Protected: Visible within the package and inherited by subclasses, promoting controlled inheritance.

*. Explain the concept of a static method in Java and its significance.

A static method in Java is a method that belongs to the class itself rather than an object of the class. Here are the key characteristics and significance of static methods:

- Class-Level Association: Static methods are defined with the

statickeyword and are associated with the class, not its instances. You can call them directly using the class name without needing to create an object first. (e.g.,Math.sqrt(4)). - No Access to Instance Variables: Static methods cannot directly access non-static (instance) variables of the class, as they are not tied to a specific object’s state.

- Can Access Static Variables: They can access static variables (class variables) that belong to the class itself.

- Utility Methods: Static methods are often used for utility functions that don’t require modifying object state. Examples include mathematical calculations (like

Math.sqrt()), conversions (Integer.parseInt()), or helper functions specific to the class. - Early Execution: The JVM typically executes static methods before creating class instances, making them suitable for initialization tasks or accessing class-level constants.

- Improved Efficiency: Since static methods don’t involve object creation overhead, they can potentially be more efficient for frequently called utility functions.

Significance:

- Code Reusability: Static methods promote code reusability by providing functionality that can be used by any object of the class without redundancy.

- Improved Readability: Calling a static method using the class name often improves code readability, especially for utility functions that don’t rely on object state.

- Class-Level Logic: Static methods are useful for encapsulating logic related to the class itself, such as validation routines or helper functions.

In summary, static methods are a powerful tool in Java for creating reusable utility functions, improving code organization, and potentially enhancing efficiency. They are well-suited for tasks that operate on class-level data or don’t require modifying object state.

*. Can you override a private or static method in Java?

No, you cannot override a private or static method in Java. Here’s why for each case:

Private Methods:

- Reason: Private methods are encapsulated within a class and hidden from subclasses.

- Inheritance: Inheritance establishes a relationship between classes where a subclass inherits members from its superclass. Since private members are hidden, they are not part of the inheritance contract.

- Override Attempt: If you try to override a private method in a subclass, it would essentially be creating a new method with the same signature within the subclass, not overriding an inherited one.

Static Methods:

- Reason: Static methods are associated with the class itself, not objects. They are resolved at compile time based on the class name used in the call.

- Override vs. Overload: Overriding involves redefining a method in a subclass that has the same signature (name and parameter list) as a method in the superclass. Static methods, however, cannot be overridden because they are not part of the object’s behavior. Calling a static method with the subclass name would still call the method in the superclass.

- Similar Functionality: If you need similar functionality in a subclass, you can create a new static method with a different name in the subclass.

Here’s an analogy:

Imagine a private method as a blueprint hidden inside a house (the class). Subclasses (extensions) cannot access or modify these internal blueprints. Similarly, static methods are like features of the house exterior (the class) that are accessed directly without needing to enter a specific house instance (object). You cannot “override” the exterior features by extending the house.

Alternatives:

- If you need to share functionality between classes but want to restrict access, consider using protected methods. These are inherited by subclasses but remain accessible only within the package or by subclasses themselves.

- If you need similar functionality specific to a subclass, create a new static method with a different name within the subclass.

*. Could you elaborate on the usage of ‘this’ and ‘super’ keywords in Java?

The this and super keywords in Java are fundamental for object manipulation and navigating class hierarchies. Here’s a breakdown of their usage:

this Keyword:

- Reference to Current Object: The

thiskeyword refers to the current object instance itself within a method or constructor. It is used to distinguish between instance variables and method parameters that might have the same name.

Usages:

-

Accessing Instance Variables: When a method needs to access an instance variable (attribute) that has the same name as a method parameter, you use

thisto clarify that you’re referring to the object’s variable.public class Person { private String name; public void setName(String name) { this.name = name; // this.name refers to the object's name attribute } } -

Calling Other Constructors: You can use

thisto call other constructors within the same class during object creation. This is useful for constructor overloading.public class Car { private String model; public Car(String model) { this.model = model; } public Car(int year) { this("Unknown"); // Call the other constructor with default model // Additional logic specific to year } } -

Returning the Current Object: You can use

thisto return the current object instance from a method. This is often used for method chaining (calling multiple methods on the same object consecutively).public class StringBuilder { private String value; public StringBuilder append(String str) { value += str; return this; // Return the current StringBuilder object for chaining } }

super Keyword:

- Reference to Superclass: The

superkeyword refers to the immediate superclass of the current class. It is used to call methods or access constructors defined in the superclass.

Usages:

-

Calling Superclass Methods: You can use

superto call methods defined in the superclass from within a subclass method. This is useful when you want to leverage the superclass’s implementation and potentially add your own logic afterward (method overriding).public class Animal { public void makeSound() { System.out.println("Generic animal sound"); } } public class Dog extends Animal { @Override public void makeSound() { super.makeSound(); // Call the superclass's makeSound first System.out.println("Woof!"); } } -

Calling Superclass Constructors: You can use

superto call the superclass constructor from within a subclass constructor. This is important for proper object initialization and ensures the superclass’s constructor gets called first.public class Person { private String name; public Person(String name) { this.name = name; } } public class Student extends Person { private String id; public Student(String name, String id) { super(name); // Call the superclass constructor with name this.id = id; } }

Key Points:

- Both

thisandsupermust be used within non-static contexts (methods or constructors). thisis used for within-class references, whilesuperis used for superclass interactions.

By effectively using this and super, you can write clean, maintainable, and well-structured Java code that leverages object-oriented programming principles.

*. Discuss the immutability of Strings in Java and the reasons behind it.

In Java, strings are immutable, meaning once a String object is created, its content cannot be changed. Any attempt to modify an existing String object will result in a new String object being created with the updated content. Here’s a breakdown of immutability in Java Strings and the reasons behind it:

Immutability of Strings:

- String Pool: Java maintains a String pool in memory. When you create a String literal (e.g., “hello”), the JVM checks the pool first. If an identical String already exists, the reference to the existing object is returned. Otherwise, a new String object is created in the pool.

- Fixed Content: Once a String object is created, its character data becomes final. Any methods that appear to modify a String (like

concatorreplace) actually create a new String object with the changes. The original String remains unmodified.

Reasons for Immutability:

- Thread Safety: Since Strings are immutable, multiple threads can access the same String object concurrently without worrying about data corruption. This simplifies thread synchronization and reduces the risk of race conditions.

- Security: Immutability prevents accidental or malicious modification of String content, enhancing data integrity. For example, if a password is stored as a String, immutability safeguards it from unauthorized changes.

- Performance Optimization: The String pool can improve performance by reusing existing String objects. Additionally, immutable Strings allow for efficient caching techniques based on their content.

- Declarative Nature: Immutability aligns with a declarative programming style where you focus on “what” the String should be, not how it should be modified. This can lead to cleaner and more predictable code.

Example:

String str1 = "Hello";

String str2 = str1.concat(" World"); // str2 points to a new String object

System.out.println(str1); // Prints "Hello" (original unchanged)

System.out.println(str2); // Prints "Hello World" (new String)

Alternatives for Modification:

While you cannot modify an existing String object, you can achieve similar results by:

- Creating a New String: As demonstrated above, methods like

concatorreplacereturn a new String object with the modifications. - StringBuilder: For scenarios requiring frequent modifications, consider using the

StringBuilderclass. It’s mutable and allows for efficient character manipulation.

In Summary:

String immutability in Java is a deliberate design choice that offers several benefits, including thread safety, security, performance optimization, and a more declarative programming style. Understanding and effectively utilizing String immutability is essential for writing robust and efficient Java applications.

*. Discuss Stringbuffer vs Stringbuilder vs string

All right, here’s a breakdown of String, StringBuffer, and StringBuilder in Java, explaining their functionalities, immutability, and use cases with code examples:

1. String:

- Immutable: Strings are immutable, meaning their content cannot be changed after creation.

- Thread-safe: Since they are immutable, multiple threads can safely access the same String object without data corruption concerns.

- Use cases: Ideal for scenarios where the String content remains constant, like storing names, constant messages, or configuration values.

Code Example:

String name = "Alice";

// name = name.concat(" Bob"); // This would create a new String object

name = new String(name.concat(" Bob")); // Create a new String explicitly

System.out.println(name); // Prints "Alice Bob"

2. StringBuffer:

- Mutable: StringBuffer is a thread-safe mutable string buffer class. You can modify its content using methods like

append,insert, andreplace. - Thread-safe: Multiple threads cannot access a StringBuffer concurrently and modify it safely without proper synchronization.

- Use cases: When you need to build a String dynamically by performing multiple modifications, especially in a multi-threaded environment.

Code Example:

StringBuffer message = new StringBuffer("Hello");

message.append(" World");

message.insert(5, " from ");

System.out.println(message); // Prints "Hello from World"

3. StringBuilder:

- Mutable: Similar to StringBuffer, StringBuilder is a mutable string builder class for efficient string manipulation.

- Non-thread-safe: Unlike StringBuffer, StringBuilder is not thread-safe. If multiple threads access and modify a StringBuilder concurrently, you need to implement synchronization to avoid data corruption.

- Use cases: When you need a mutable string builder class for performance-critical operations in single-threaded environments. StringBuilder is generally faster than StringBuffer due to the lack of synchronization overhead.

Code Example:

StringBuilder address = new StringBuilder();

address.append("123 Main St");

address.append(", Apt. 5");

System.out.println(address); // Prints "123 Main St, Apt. 5"

Choosing Between Them:

- Immutability: Use String if the content remains constant.

- Thread Safety: If thread safety is crucial, use StringBuffer.

- Performance: If thread safety is not a concern and performance is critical in a single-threaded environment, use StringBuilder.

In Summary:

String, StringBuffer, and StringBuilder offer different trade-offs between immutability, thread safety, and performance. By understanding their characteristics and use cases, you can choose the most appropriate option for your specific Java programming needs.

*. Implement your own immutable class in Java.

Here’s an example of an immutable class in Java:

public final class Point {

private final int x;

private final int y;

public Point(int x, int y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public int getX() {

return x;

}

public int getY() {

return y;

}

// Don't provide setter methods for x and y

// Create a new Point object with a new location (useful for immutability)

public Point move(int deltaX, int deltaY) {

return new Point(x + deltaX, y + deltaY);

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object o) {

if (this == o) return true;

if (o == null || getClass() != o.getClass()) return false;

Point point = (Point) o;

return x == point.x && y == point.y;

}

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash(x, y);

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Point{" + x + ", " + y + '}';

}

}

This Point class represents a point in a two-dimensional space with immutable x and y coordinates. Here’s a breakdown of the key aspects:

- Final Class: The class is declared as

finalto prevent subclassing and accidental modification of the immutability behavior. - Final Fields: The

xandyfields are declared asfinal. Once assigned during object creation, their values cannot be changed. - No Setter Methods: The class doesn’t provide setter methods for

xandy. This enforces immutability by preventing direct modification of the coordinates. moveMethod: Instead of modifying the current object, this method creates a newPointobject with the updated coordinates based on the provided deltas. This allows for creating new points with different locations while maintaining the immutability of the original object.equalsandhashCode: These methods are overridden to provide proper equality and hash code functionality based on the immutable x and y coordinates.toString: This method provides a meaningful string representation of thePointobject.

By following these principles, you can create immutable classes in Java that promote data integrity, thread safety (as there’s no concurrent modification risk), and better reasoning about object state.

*. Compare and contrast shallow cloning and deep cloning in Java, providing examples.

Shallow Cloning:

In shallow cloning, a new object is created, but only the top-level fields of the original object are duplicated. If the object contains references to other objects, those references are copied, but the actual objects are not cloned. As a result, changes made to the cloned object’s nested objects will also affect the original object’s nested objects, and vice versa.

Example of Shallow Cloning:

class Person implements Cloneable {

private String name;

private Address address;

public Person(String name, Address address) {

this.name = name;

this.address = address;

}

// Getter and setter methods

@Override

public Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException {

return super.clone();

}

}

class Address {

private String city;

public Address(String city) {

this.city = city;

}

// Getter and setter methods

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) throws CloneNotSupportedException {

Address address = new Address("New York");

Person originalPerson = new Person("Alice", address);

// Shallow clone

Person clonedPerson = (Person) originalPerson.clone();

// Modify the cloned person's address

clonedPerson.getAddress().setCity("Los Angeles");

// Output the original person's address

System.out.println(originalPerson.getAddress().getCity()); // Output: Los Angeles

}

}

In this example, when the originalPerson is cloned, a new clonedPerson object is created. However, both originalPerson and clonedPerson share the same Address object. Therefore, when the address of clonedPerson is modified, it also affects the address of originalPerson.

Deep Cloning:

In deep cloning, not only the top-level fields of the original object are duplicated, but all the nested objects are recursively cloned. This means that changes made to the cloned object’s nested objects will not affect the original object’s nested objects, and vice versa.

Example of Deep Cloning:

class Person implements Cloneable {

private String name;

private Address address;

public Person(String name, Address address) {

this.name = name;

this.address = address;

}

// Getter and setter methods

@Override

public Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException {

Person clonedPerson = (Person) super.clone();

clonedPerson.address = (Address) address.clone(); // Deep clone the Address object

return clonedPerson;

}

}

class Address implements Cloneable {

private String city;

public Address(String city) {

this.city = city;

}

// Getter and setter methods

@Override

public Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException {

return super.clone();

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) throws CloneNotSupportedException {

Address address = new Address("New York");

Person originalPerson = new Person("Alice", address);

// Deep clone

Person clonedPerson = (Person) originalPerson.clone();

// Modify the cloned person's address

clonedPerson.getAddress().setCity("Los Angeles");

// Output the original person's address

System.out.println(originalPerson.getAddress().getCity()); // Output: New York

}

}

In this example, when the originalPerson is cloned, a new clonedPerson object is created with a deep copy of the Address object. Therefore, changes made to the address of clonedPerson do not affect the address of originalPerson.

*. What happens when you override both the ‘equals’ and ‘hashCode’ methods in Java? What if ‘hashCode’ returns the same value while ‘equals’ returns false?

When you override both the equals and hashCode methods in Java, you ensure consistency between these methods, which is crucial when using objects in collections like HashMap, HashSet, etc.

When Both equals and hashCode are Overridden:

-

Consistency: Objects that are considered equal according to the

equalsmethod must have the same hash code according to thehashCodemethod. This ensures consistency when objects are used in hash-based collections. -

Performance: Overriding

hashCodemethod is important for performance in hash-based collections. It ensures that objects that are “equal” (as per theequalsmethod) are likely to be stored in the same hash bucket, which reduces the time complexity of operations like searching and retrieval.

What if hashCode Returns the Same Value While equals Returns False?

If hashCode returns the same value for two objects that are not considered equal according to the equals method, it can lead to unexpected behavior when these objects are used in hash-based collections:

-

Hash Collision: When different objects produce the same hash code, they are stored in the same hash bucket in a hash-based collection. This results in a hash collision.

-

Search Complexity: When searching for an object in a hash-based collection, the collection needs to iterate over all objects in the same hash bucket to find the matching object. This can degrade the performance of hash-based operations.

-

Inconsistency: Since

equalsreturnsfalsefor these objects, they should not be considered equal. However, because they have the same hash code, they are stored in the same hash bucket, leading to inconsistency in the behavior of hash-based collections.

Example:

public class Person {

private String name;

private int age;

public Person(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

if (obj == null || getClass() != obj.getClass()) return false;

Person person = (Person) obj;

return age == person.age && Objects.equals(name, person.name);

}

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash(name); // Hash code based only on name

}

}

In this example, if two Person objects have the same name but different ages, they will have the same hash code (based on name), but equals will return false. This can lead to hash collisions and inconsistent behavior in hash-based collections.

Summary:

- Overriding both

equalsandhashCodemethods ensures consistency and performance when objects are used in hash-based collections. - If

hashCodereturns the same value whileequalsreturnsfalse, it can lead to hash collisions and inconsistent behavior in hash-based collections. It’s important to ensure thatequalsandhashCodeare consistent to maintain the correctness and performance of hash-based operations.

*. Explain Comparator and comparable in JAVA 8, with code example. Give difference in table.

In Java, Comparable and Comparator are two interfaces used for sorting objects. Both provide ways to determine the order of objects, but they have different use cases and methods of implementation.

Comparable

Comparable is used to define the natural ordering of objects. A class that implements Comparable must override the compareTo method, which compares this object with the specified object for order.

Example of Comparable

public class Person implements Comparable<Person> {

private String name;

private int age;

public Person(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

@Override

public int compareTo(Person other) {

return this.age - other.age; // Compare based on age

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return name + " (" + age + ")";

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<Person> people = new ArrayList<>();

people.add(new Person("Alice", 30));

people.add(new Person("Bob", 25));

people.add(new Person("Charlie", 35));

Collections.sort(people);

people.forEach(System.out::println);

}

}

Comparator

Comparator is used to define custom orderings of objects. It can be implemented as a separate class, allowing multiple different comparisons for the same type of objects. Java 8 introduced lambda expressions and method references, which make using Comparator more concise.

Example of Comparator

import java.util.*;

public class Person {

private String name;

private int age;

public Person(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return name + " (" + age + ")";

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<Person> people = new ArrayList<>();

people.add(new Person("Alice", 30));

people.add(new Person("Bob", 25));

people.add(new Person("Charlie", 35));

// Sort by age using Comparator

people.sort(Comparator.comparingInt(p -> p.age));

people.forEach(System.out::println);

// Sort by name using Comparator with method reference

people.sort(Comparator.comparing(Person::getName));

people.forEach(System.out::println);

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

}

Difference Between Comparable and Comparator

| Feature | Comparable |

Comparator |

|---|---|---|

| Package | java.lang |

java.util |

| Method | compareTo(Object o) |

compare(Object o1, Object o2) |

| Usage | Natural ordering | Custom ordering |

| Implementation | Class implements Comparable |

Separate class or lambda expression |

| Single vs Multiple | Single comparison logic | Multiple comparison logics |

| Code Modification | Modifies the class whose objects are being compared | Does not modify the class being compared |

| Java 8 Enhancements | Not directly affected | Enhanced with lambda expressions and method references |

Summary

- Use

Comparable: When you want to define a single, natural ordering for objects of a class. The class itself implements theComparableinterface and defines thecompareTomethod. - Use

Comparator: When you need multiple ways to compare objects, or when you cannot modify the class whose objects you want to sort. Java 8’s lambda expressions and method references make it easier and more flexible to create comparator instances.

Additional Notes

- Comparable: Best used for objects that have one logical order.

- Comparator: Provides more flexibility and can be used to create multiple different orderings for objects. Ideal for use cases where the ordering logic can change or needs to be dynamic.

*. What are the different types of functional interfaces in java ?

In Java, a functional interface is an interface that contains only one abstract method. Functional interfaces are a key concept in Java’s functional programming paradigm, particularly with the introduction of lambda expressions in Java 8. There are several types of functional interfaces in Java, and some of the commonly used ones include:

- java.lang.Runnable: Represents a task that can be executed asynchronously.

- java.util.concurrent.Callable: Represents a task that returns a result and may throw an exception.

-

java.util.Comparator: Represents a function that compares two arguments for order.

-

java.util.function.Function: Represents a function that accepts one argument and produces a result.

-

java.util.function.Predicate: Represents a predicate (boolean-valued function) of one argument.

-

java.util.function.Consumer: Represents an operation that accepts a single input argument and returns no result.

-

java.util.function.Supplier: Represents a supplier of results.

-

java.util.function.UnaryOperator: Represents an operation on a single operand that produces a result of the same type as its operand.

- java.util.function.BinaryOperator: Represents an operation upon two operands of the same type, producing a result of the same type as the operands.

These functional interfaces provide a foundation for working with lambda expressions and functional programming constructs in Java, enabling concise and expressive code. They are widely used in APIs like the Streams API and in many other scenarios where functional programming paradigms are applicable.

*. How do you invoke lambda function ?

In Java, you can invoke a lambda function by assigning it to a functional interface reference and then calling the method defined in that functional interface. Lambda expressions provide a concise way to represent anonymous functions, especially when working with functional interfaces. Here’s an example of invoking a lambda function:

public class LambdaExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Define a lambda expression for a Runnable functional interface

Runnable runnable = () -> System.out.println("Executing runnable lambda");

// Invoke the lambda function by calling the method defined in the functional interface

runnable.run();

// Define a lambda expression for a Comparator functional interface

Comparator<Integer> comparator = (a, b) -> a.compareTo(b);

// Invoke the lambda function by calling the method defined in the functional interface

int result = comparator.compare(5, 10);

System.out.println("Comparison result: " + result);

}

}

In this example:

-

We define a lambda expression for the

Runnablefunctional interface, which represents a task that can be executed asynchronously. The lambda expression( ) -> System.out.println("Executing runnable lambda")is a shorthand way to implement therunmethod of theRunnableinterface. -

We assign the lambda expression to a reference of type

Runnablenamedrunnable. -

We invoke the lambda function by calling the

runmethod defined in theRunnableinterface using therunnable.run()syntax. -

Similarly, we define a lambda expression for the

Comparatorfunctional interface, which represents a function for comparing two objects. The lambda expression(a, b) -> a.compareTo(b)compares two integers. -

We assign the lambda expression to a reference of type

Comparator<Integer>namedcomparator. -

We invoke the lambda function by calling the

comparemethod defined in theComparatorinterface using thecomparator.compare(5, 10)syntax.

Lambda expressions provide a concise and expressive way to implement functional interfaces, making it easier to work with functional programming constructs in Java.

*. How is the diamond problem resolved in interfaces after Java 8?

In Java, the diamond problem refers to a scenario in multiple inheritance where a class implements two interfaces, both of which have a default method with the same signature. This creates ambiguity about which default method should be invoked by the implementing class.

Prior to Java 8, Java did not allow multiple inheritance through classes, but it was still possible through interfaces. However, starting from Java 8, interfaces support default methods, which could potentially lead to the diamond problem if two interfaces with conflicting default methods were implemented by a class.

To resolve the diamond problem in interfaces after Java 8, Java introduced the following rules:

-

Class Takes Precedence: If a class inherits a method with the same signature from both a superclass and an interface, the method in the class takes precedence.

-

Interface Method Hiding: If a class inherits a method with the same signature from two interfaces, the class must explicitly implement the method or provide its own implementation to resolve the conflict. The method from one of the interfaces can be invoked using

InterfaceName.super.method()syntax. -

Interface Method Overriding: If a class inherits a method with the same signature from two interfaces, it can override the method and provide its own implementation. However, this approach should be used with caution as it could potentially break the contract of one or both interfaces.

These rules ensure that the diamond problem is effectively resolved in interfaces after Java 8, providing clarity on method resolution and avoiding ambiguity in multiple inheritance scenarios.

Here’s a simple example illustrating how the diamond problem is resolved in interfaces after Java 8:

interface InterfaceA {

default void display() {

System.out.println("InterfaceA");

}

}

interface InterfaceB extends InterfaceA {

default void display() {

System.out.println("InterfaceB");

}

}

class MyClass implements InterfaceB {

// Resolves the conflict by providing its own implementation

@Override

public void display() {

InterfaceB.super.display(); // Invokes the default method from InterfaceB

// Additional implementation if needed

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

MyClass obj = new MyClass();

obj.display(); // Output: InterfaceB

}

}

In this example, InterfaceA and InterfaceB both have a default display() method with the same signature. The MyClass implements InterfaceB, and it resolves the conflict by providing its own implementation of the display() method.

*. Differentiate between abstract classes and interfaces in Java, discussing their respective use cases.

Both abstract classes and interfaces are key concepts in Java used for abstraction and defining contracts. However, they have different characteristics and are used in different scenarios.

Abstract Classes:

-

Characteristics:

- Abstract classes are classes that cannot be instantiated on their own and may contain abstract methods.

- Abstract methods are methods without a body (implementation) and are declared with the

abstractkeyword. - Abstract classes can contain both abstract and concrete methods.

-

Use Cases:

- Abstract classes are used when a common base implementation is required for a group of related classes.

- They provide a way to define common methods and fields that subclasses can inherit and override.

- Abstract classes are useful for creating hierarchies where some methods have a default implementation, and subclasses can provide specific implementations for certain methods.

-

Example:

abstract class Shape { // Abstract method to calculate area public abstract double calculateArea(); // Concrete method to display shape information public void display() { System.out.println("This is a shape."); } }

Interfaces:

-

Characteristics:

- Interfaces are like contracts that define a set of methods without providing any implementation.

- All methods in an interface are implicitly

publicandabstract(prior to Java 8), or they can bedefaultorstaticmethods (from Java 8 onwards). - Classes implement interfaces to provide specific implementations for the methods defined in the interface.

-

Use Cases:

- Interfaces are used when you want to define a contract that multiple classes can implement.

- They provide a way to achieve multiple inheritance of type, as a class can implement multiple interfaces but can only extend one class.

- Interfaces are widely used in Java APIs for defining behavior that can be implemented by different classes.

-

Example:

interface Drawable { void draw(); }

Comparison:

-

Instantiation:

- Abstract classes cannot be instantiated directly, while interfaces cannot be instantiated at all.

-

Inheritance:

- A class can extend only one abstract class but can implement multiple interfaces.

- Abstract classes can have constructors, instance variables, and non-abstract methods, while interfaces cannot.

-

Default Implementation:

- Abstract classes can provide default implementations for some methods, while interfaces can only declare methods without providing implementations (before Java 8).

-

Use Cases:

- Use abstract classes when you want to provide a common base implementation or when you need to define non-public members.

- Use interfaces when you want to define a contract for classes to implement or when you need to achieve multiple inheritance of type.

In summary, abstract classes and interfaces are both used for abstraction and defining contracts, but they have different characteristics and are used in different scenarios based on the requirements of the design.

*. What is marker interface ?

A marker interface in Java is an interface that does not contain any methods or members. Its sole purpose is to mark or tag a class as having some special behavior or capability. Marker interfaces are also known as tag interfaces.

Characteristics of Marker Interfaces:

-

Empty: Marker interfaces do not contain any methods or members. They serve as a form of metadata attached to a class.

-

Used for Identification: Marker interfaces are used to indicate that a class implementing the interface possesses certain characteristics or capabilities.

-

Compile-Time Check: The presence or absence of a marker interface is typically checked at compile time rather than at runtime.

-

Convention: Marker interfaces are a convention rather than a language feature. They rely on developers adhering to the convention and implementing the necessary behavior in the marked classes.

Example Use Cases:

-

Serializable Interface:

java.io.Serializableis a marker interface used to indicate that a class is serializable, meaning its objects can be converted into a stream of bytes and then restored back to objects. -

Clonable Interface:

java.lang.Cloneableis a marker interface used to indicate that a class supports object cloning, meaning its objects can be copied to create new objects. -

Remote Interface: In Java’s Remote Method Invocation (RMI),

java.rmi.Remoteis a marker interface used to indicate that a class can be accessed remotely.

Example of a Marker Interface:

// Marker interface for printable objects

public interface Printable {

// No methods

}

// Class implementing the Printable marker interface

public class Book implements Printable {

private String title;

public Book(String title) {

this.title = title;

}

public void print() {

System.out.println("Printing book: " + title);

}

}

In this example, Printable is a marker interface with no methods. The Book class implements the Printable interface, indicating that instances of Book are printable objects. The presence of the Printable interface serves as a marker indicating that certain behavior, in this case, printing, is supported by the Book class.

Marker interfaces provide a way to add metadata or mark certain classes for special handling without requiring any additional methods or fields. However, their use has diminished with the introduction of annotations in Java.

*. How to create a custom annotation?

To create a custom annotation in Java, you define a new interface and annotate it with the @interface keyword. This interface serves as the definition of the custom annotation, specifying its name, elements, and optional default values. Here’s how you can create a custom annotation:

import java.lang.annotation.ElementType;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

import java.lang.annotation.Target;

// Define a custom annotation named MyAnnotation

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME) // Specifies annotation retention policy

@Target(ElementType.METHOD) // Specifies where the annotation can be applied

public @interface MyAnnotation {

// Define elements of the annotation (optional)

String value() default ""; // Default value for the annotation element

int priority() default 0; // Default value for another annotation element

}

In this example:

-

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME): This annotation specifies the retention policy of the custom annotation. In this case,RetentionPolicy.RUNTIMEindicates that the annotation will be retained at runtime and can be accessed via reflection. -

@Target(ElementType.METHOD): This annotation specifies where the custom annotation can be applied. In this case,ElementType.METHODindicates that the annotation can only be applied to methods. -

public @interface MyAnnotation: This line defines the custom annotation namedMyAnnotation. Annotations are declared using the@interfacekeyword. -

String value() default "";: This line defines an element namedvaluefor the annotation. Elements are similar to methods and can have default values. If no value is specified for this element when using the annotation, it defaults to an empty string. -

int priority() default 0;: This line defines another element namedpriorityfor the annotation, which also has a default value of 0.

After defining the custom annotation, you can use it by applying it to elements in your code, such as classes, methods, fields, etc. Here’s an example of how to use the MyAnnotation annotation on a method:

public class MyClass {

// Apply the custom annotation to a method

@MyAnnotation(value = "CustomAnnotationExample", priority = 1)

public void myMethod() {

// Method implementation

}

}

In this example, the MyAnnotation annotation is applied to the myMethod() method with specified values for its elements (value and priority).

*. Explain Thread Lifecycle.

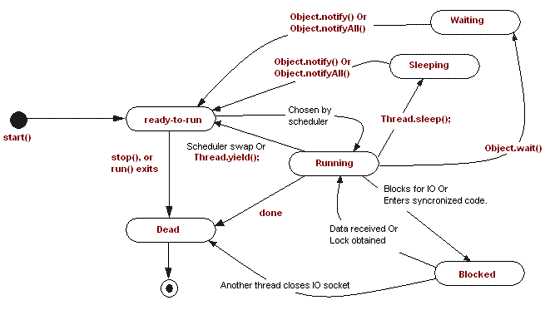

In Java, a thread undergoes several phases during its lifecycle. These phases represent the different states a thread can be in from its creation to its termination. Understanding these phases is crucial for effective multithreaded programming. The phases of a thread lifecycle in Java are as follows:

- New (Born)

- Runnable (Ready to run)

- Blocked

- Waiting

- Timed Waiting

- Terminated (Dead)

Phases of Thread Lifecycle

-

New (Born)

- Description: When a thread is created, it is in the new state. In this state, the thread is instantiated but not yet started.

- Example:

Thread t = new Thread(() -> { // Task to be performed });

-

Runnable (Ready to run)

- Description: A thread enters the runnable state when the

start()method is called. In this state, the thread is ready to run and is waiting for CPU time. It can move between the runnable state and running state. - Example:

t.start();

- Description: A thread enters the runnable state when the

-

Blocked

- Description: A thread enters the blocked state when it tries to access a protected section of code that is currently locked by another thread. It will remain in this state until the lock is released.

- Example:

synchronized (someObject) { // Protected code }

-

Waiting

- Description: A thread enters the waiting state when it is waiting indefinitely for another thread to perform a particular action. This can occur when

wait(),join(), orpark()methods are called without a timeout. - Example:

synchronized (someObject) { someObject.wait(); // Thread waits here }t.join(); // Current thread waits for t to finish

- Description: A thread enters the waiting state when it is waiting indefinitely for another thread to perform a particular action. This can occur when

-

Timed Waiting

- Description: A thread is in the timed waiting state when it is waiting for a specified amount of time. This can occur when

sleep(),wait(),join(), orparkNanos()/parkUntil()methods are called with a timeout. - Example:

Thread.sleep(1000); // Thread sleeps for 1000 millisecondssynchronized (someObject) { someObject.wait(1000); // Wait for 1000 milliseconds }t.join(1000); // Wait for t to finish or for 1000 milliseconds

- Description: A thread is in the timed waiting state when it is waiting for a specified amount of time. This can occur when

-

Terminated (Dead)

- Description: A thread enters the terminated state when it has completed its task or when it is explicitly terminated. Once a thread is in this state, it cannot be restarted.

- Example: